Concussion Crisis

Story by Isabella Ferguson

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) is a neuro-degenerative condition, seen in athletes and military personnel who have suffered multiple blows to the head.

CTE can only be diagnosed after death and there is no treatment available for symptoms that are “similar to those of early-onset dementia,” as well as “behavioural and cognitive impairment”.

Although still being investigated, there is a mounting body of evidence showing the consequences of multiple blows to the head in several football codes.

The AFL implemented a new and more serious policy on concussion this year, in response to growing concerns about the concussion crisis and research conducted by the AFL Medical Officers Association: “if in doubt, sit them out”.

“For the AFL, it’s about player health and welfare and being conservative in an environment where there’s a lot of questions floating around about the long-term consequences of head injuries,” stated the AFL’s Chief Medical Officer, Dr Peter Harcourt.

However, as this policy is only new it is possible older players are at risk of developing CTE as they did not play with the more restrictive policy.

A number of retired AFL and rugby players, including two-time Brownlow medallist Greg Williams, have come out revealing they are symptomatic, and some have also revealed their intensions to donate their brains to CTE studies.

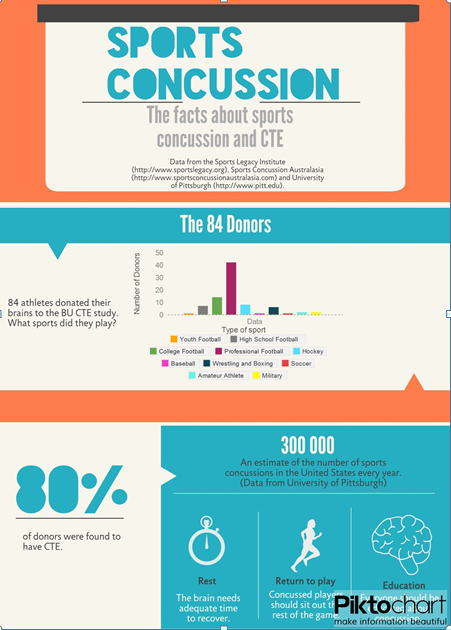

The Boston University Centre for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy (BU CSTE) has studied the donated brains of 84 athletes, who played a variety of sports before their deaths.

“Being a brain donor is similar to being an organ donor, and the procedure is done in such a way that the donor may have an open casket is desired,” stated the BU CSTE.

“BU CSTE personnel understand that this is a difficult time for the family of the donor, and they work hard to make the donation process as easy as possible for the family.”

Of the donors, 80 per cent showed evidence of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy.

The centre work in co-operation with the Sports Legacy Institute, and have a donor registry, for people and their families to donate their brain and/or spinal cord to the CTE study after death.

The Sports Legacy Institute want to “solve the concussion crisis” through advocacy, education, policy development, and medical research.

They work closely with the families of brain donors, who are invited to the Family Advisory board which assists in the running of the BU CSTE and Sports Legacy Institute.

“We are forever thankful to the families that continue to put their trust in SLI and the BU CSTE. Without their selfless contributions, SLI would have never made progress toward discovery,” wrote the Sports Legacy Institute.

IssyThe issue of CTE and concussion has become a greater presence in the sporting world, with new medical research and a lawsuit filed against the NFL in the United States involving over 4000 retired players.

The remaining family of a number of players who took their own lives were also involved in the court case, including that of 50 year old Dave Duerson, who left a note asking that his brain be donated to the CSTE.

Mr Duerson was later found to have CTE.

The plaintiffs alleged that the NFL was negligent towards the players’ injuries and their future consequences.

David Frederick, the head lawyer, accused the NFL of not recognising the impact of multiple concussive injuries.

“The league knew or should have known that these repeated blows to the head caused significant neurological injury,” said Mr Frederick.

One retired player, Kevin Turner, 43, suffers from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (A.L.S), which he believes is connected to concussions obtained during his career.

Mr Turner was told by the NFL that there was no connection.

THERE are fears Australian footballers could be left with a degenerative brain condition following a recent US court case and admissions by a retired AFL player.

“The NFL was acting like we were idiots, that there was no correlation,” he said.

The NFL settled with the plaintiffs in late August for $375 million, pledging to do more to help retired players, and make the game safer for all involved.

The lawsuit has also prompted Australian sporting codes, to question whether they would be liable for a similar case in the future.

The “Concussion in Sport” conference was recently held in Melbourne, bringing together three major Australian sporting codes, and the medical community to discuss the concussion crisis and what the codes can do to educate the community and increase player safety in the game.

The difficulty of CTE is that it can only be diagnosed post-mortem, meaning it is possible that symptomatic people have a mental illness or dementia.

Although CTE has undergone substantial research, some researchers have argued that the debate has been played out through the media.

“Unfortunately, this debate has largely been played out in the news media rather than through scientific journals,” wrote Professor Andrew Kaye, Director of Neurosurgery at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

“Complex issues have been oversimplified and distorted, causing significant alarm… and concern over how an acute injury should be managed.”

“…rather than driving the debate through the media, the issues raised need to be tested in the cold light of scientific peer review.”

Although most attention about CTE is focused on professional athletes, there are concerns about its effects on children playing sport – the youngest donor to the CSTE study was youth football player Isaac Harding, 14.

In a 2012 interview with ABC’s Four Corners, Jeffrey Rosenfeld, the Director of Neurosurgery at Victoria’s Alfred Hospital, said that sporting codes should implement a “three strikes and you’re out” style policy.

“I personally would say three significant concussions, three strikes and you’re out. That’s what I would say.”

Helmets while the obvious solution, have been found to give no protection from concussion, and research has found they can lead to players taking more risks and partaking in more aggressive play.

While the issue of CTE continues to be debated, one thing is clear: sporting codes must do more to prevent the concussion crisis from becoming far greater than it currently is.

If you or someone you know is currently experiencing suicidal thoughts, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Mensline on 1300 78 99 78