Politicians Hinder Refugee Resettlement

Story by Kai Hayes

REFUGEES in Australia are initially struggling to find employment and integrate into the community, and politicians aren’t helping, settlement assistance organisations say.

Kefayet Mohammed, who is Rohingya, was accepted into Australia as a refugee fleeing persecution from Burma four years ago.

The Rohingya people originate from the Rahkine State in West Burma, where Kefayet says life was horrible for the ethnic minority.

“We faced religious and racial persecution with forced labour, no freedom of movement, rape, arbitrary areas, and we were persecuted every day in life,” he said.

Kefayet spent most of his childhood in a Bangladesh refugee camp.

“The lifestyle here’s totally different to where I am from, in Bangladesh one of the most terrible places in the world, with no access to health, in one of the poorest countries in the world.”

He says upon arrival in Australia it was a tough slog until he could find employment.

“When I came here first, I struggled for work, and because of that, I struggled for everything.”

The Australian Refugee Association (ARA) assists more than 400 clients a year with writing resumes, interview skills and learning English.

Only 40 percent of their clients are able to find work placement.

Similarly, the Brisbane based Multicultural Development Association (MDA) assists with housing and settlement services.

MDA media and communications manager Akua Ahenkorah says while most struggle to find jobs, those that do are able to maintain them.

“A lot of them are doing the jobs that most average Australians aren’t doing,” Ms Ahenkorah said.

“The entire staff of Emerald McDonalds is asylum seekers.”

“They needed a job, one of them was an engineer, but his qualifications weren’t recognised here,” she said.

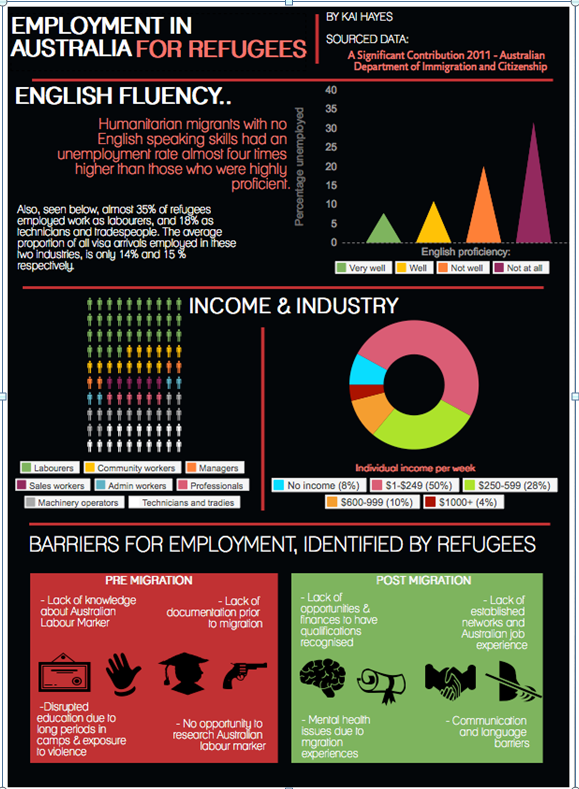

A 2011 Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship report by University of Adelaide demographer, Professor Graeme Hugo, found that almost 35 percent of humanitarian migrants employed are labourers, with another 30 percent being machine operators, labourers, technicians and tradies.

A stark contrast to the main industries those born in Australia are working in.

However, that is just for those who can find work. Unemployment rates for humanitarian entrants to Australia the 1940-70’s hovered around six percent, whereas now, they’re at almost 18 percent.

ARA community development manager Craig Heidenreich says for those who can’t find a job, English is the main barrier.

“Lack of English compounds the issue,” Mr Heidenreich said.

“When your English is lower, there is a presumption you lack intelligence, which is not the case.”

The 2011 report also found that only seven point seven percent of those who spoke English “very well” were unemployed.

KaiThose who did not speak English at all had an unemployment rate of 31.5 percent.

Mr Heidenreich says the politisiation of refugees hasn’t helped, making his job even harder.

“The frequent changes to government policy have left most people, even specialists, confused and worn out trying to work through the changes,” he said.

“Employers need certainty, and when some refugees are eligible to work and others are not, it gets confusing.”

Greens Senator Larissa Waters agrees, but blames the attitude on the Coalition, saying they have left Australian employers with a negative attitude toward refugees.

“The Abbott Government won’t speak about refugees as people, they are dehumanising them when they call them ‘illegals’ and it implies there is some sort of criminality involved,” Senator Waters said.

“This is a lie as it is not illegal to seek asylum in Australia and it only encourages Australians to treat these vulnerable people with cruelty.”

Several Coalition ministers were approached for comment however none responded by deadline.

Senator Waters wants more assistance given to refugees to find work.

“Refugee support services should be extended to allow enough support while they settle into the community, and refugees should be given access to the employment support services available to all Australians,” she said.

Akua, whose organisation offers such services, says industry and Government groups also need to do more to recognise qualifications, just because some aren’t from a western background.

“In some respects it is justified,” she said.

“But for some people they almost have to go back to square one, so bridging courses are a good option.”

Federal Labor MP Graham Perrett says it’s not up to Government to decide which accreditations are acknowledged in Australia.

“It’s an international process but industry is best left to industry,” Mr Perrett said.

“There’s no point a politician telling an engineer what makes a good engineer.“

However, Mr Perrett agrees that the qualification process for migrants could be easier.

“A doctor in Vietnam may not easily become a doctor in Australia, but perhaps instead of starting from scratch they could work as a nurse until the relevant qualifications are obtained, so those skills aren’t lost,” he said.

But while the Greens point the finger at the Coalition for a negative community attitude, left-wing political lobby group GetUp! says Labor and the media are just as much to blame.

GetUp!’s refugee and asylum seeker policy worker, Alycia Gawthorne, says they don’t think about potential long-term consequences.

“In reality, they are dehumanising them, often because once this is done, its quite easy to inflict inhumane policies,” Ms Gawthorne said.

“The media has a huge influence, for example, the Daily Telegraph’s headline ‘open the floodgates – thousands of boat people to invade NSW’ is hugely influential.”

But while some may struggle for work, the 2011 report found that most asylum seekers are generally happy once settled into an Australian community.

The report found 70 percent of humanitarian migrants said they felt they had been treated well in Australia, whilst 25 percent responded “sometimes”.

When asked if they were happy in Australia, 47.9 percent strongly agreed, while 38.9 percent agreed.

For Kefayet, who now works as a translator for the Multicultural Development Association, he couldn’t imagine life any other way.

“I could not dream for work, I could not dream for education, I could not dream for good health,” he said.

“But I came to Australia, and I found it.”