The world of fast fashion

Its easier to claim environmental consciousness than be it in the world of fast fashion

by Jessica Wilkie

Summary

Fast Fashion is one of the biggest polluters and waste creators. As well as being a huge detriment to the environment, shopping with fast fashion brands in also an ethically questionable decision. Only 93% of fast fashion brands paying garment workers a living wage in 2020, and there has been more landfill waste of non-biodegradable material than ever before (Weavabel, 2021). This report will discuss the devastating impact fast fashion has on the environment, the rise in popularity of fast fashion, and what steps and measures can realistically be taken to combat the issue.

Introduction

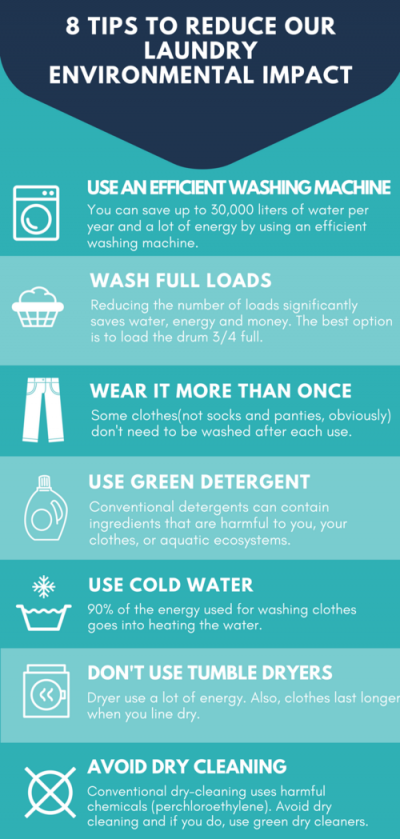

Rauturier, for Good on You blog, defines fast fashion as “cheap, trendy clothing that samples ideas from the catwalk or celebrity culture and turns them into garments in high street stores at breakneck speed to meet consumer demand” (Rauturier, 2021). They continue that the driving idea behind fast fashion brands is to get the newest styles up for sale as fast as possible. Meeting market demand as soon as it appears and therefore appealing to a large consumer base of shoppers. This production model means that often, the clothes are poorly made, and out of sub-par material. Coupling this with how fast fashion plays into the notion that outfit repeating is unacceptable, builds a toxic system of overproduction and consumption that has made fashion one of the world’s largest polluters (Rauturier, 2021). According to a report by Fixing Fashion, titled ‘textile production contributes more to climate change than international aviation and shipping combined’, the very nature of fast fashion, with the rapid rate of new trendy products being created, prevents it from ever truly being sustainable (Weavabel, 2021). Fast fashion has a long way to go before being environmentally conscious or ethical or sustainable is even in sight. Zhou, for refinery 29, claims ‘It’s no secret that the fashion industry is one of the most polluting industries out there, and that garment workers are, often, treated horrendously’ (Zhou, 2021) and goes on to suggest this is widely known across the consumer platform who are buying from fast fashion brands. Social movements are becoming more prevalent to help stop the cycle of fast fashion environmental impact. One such idea is “will I wear this 30 times”. Zhou estimates that on average, a shopper will only wear a garment 7 times before it becomes landfill. They argue that when consumers shop and buy ridiculously cheap clothes, this makes them appear disposable. The ’30 wears challenge’ was created by co-founder of Eco-Age, Livia Firth to help combat this growing issue. The idea behind it is to slow down impulse buying of fast fashion products (Zhou, 2021). (Figures one and two show other campaign materials to combat the cyclical trend of fast fashion).

Discussion

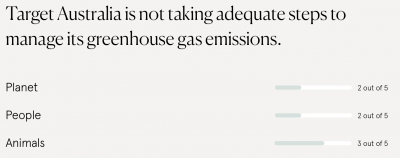

There are particulars that define fast fashion and set it apart from other fashion practises. Some of the key factors that are found in the fast fashion industry include; thousands of styles which touch on all the latest trends, an extremely short turnaround time between when a trend or garment is seen on the catwalk or in celebrity media and when it hits the shelves, offshore manufacturing where labour is the cheapest, with the use of workers on low wages without adequate rights or safety and complex supply chains with poor visibility beyond the first tier, a limited quantity of a particular garment, and cheap, low-quality materials like polyester, causing clothes to degrade after just a few wears and get thrown away (Rauturier, 2021). By these defining factors, it is important to discuss brands like Target Australia. Target Australia claims to be largely environmentally conscious and that their products are ethically sourced as purchasing decisions are often made by more educated and socially conscious shoppers based on claims like these. “Target strives to be a sustainable, ethical, and socially responsible business… to make a positive difference in all parts of our business, by minimising our environmental impact, being active members of our communities, promoting diversity and ensuring our products are sourced ethically (Target, 2021). On face value, statements like these lull consumers into a false sense of what production looks like within huge fashion corporations such as Target Australia. Paired with campaign slogans like “Target are committed to ensuring the workers who produce its products and services are treated with dignity and respect and can live and work in a safe and healthy environment” (Target, 2021), Targets sustainability and recycled materials initiatives have proved sale rates of 100-120%. However, an investigative report by Good on You has shown that Target Australia’s overall people, planet and animals rating is underwhelmingly “not good enough” and sating that Target “received a score of 31-40% in the Fashion Transparency Index… there is no evidence it ensures the necessary policy to back their claims” (Good on You, 2020). (Figures three and four).

Conclusion

As a growing population of consumers realise the true cost of fashion, there has been an increase in the number of retails who have introduced (or claim to have introduced) sustainable and ethical fashion initiatives. The underlying issue remains the speed at which fast fashion is produced as it is putting massive pressure on both people and the environment. “Recycling and small eco or vegan clothing ranges, when they are not only for greenwashing, are not enough to counter the ‘throw-away culture’, the waste, the strain on natural resources, and the myriad of other issues created by fast fashion” (Rauturier, 2021). However, there is some hope for the industry. Already there has started to be a pull away from fast fashion. Looking back to 2009, New York Fashion Week hosted its first-ever Eco Fashion Week. Steadily, there has been an increase in demand for information, transparency, and major commitments to do better from big brands and fast fashion brands. According to a report by The Business Research Company, sustainable and ethical fashion is expected to grow to $9,808.5 million in 2025 (Oliberté, 2021).

Appendices

Figures One and Two (Sustain your Style, 2020).

Figures Three and Four (Good on You, 2020).

References

Clean up Australia. 2021. Clean Up. Org. Fast Fashion. https://www.cleanup.org.au/fastfashion

Good on You. 2020. Target Australia. Target Australia is not taking adequate steps to manage its greenhouse gas emissions. https://directory.goodonyou.eco/brand/target-australia

Oliberté. 2021. Oliberté.com. Fast Fashion vs Sustainable Fashion. https://www.oliberte.com/pages/fast-fashion-vs-sustainable-fashion/

Rauturier. 2021. Good on You. The 43 most ethical and sustainable clothing brans from Australia and NZ. https://goodonyou.eco/most-ethical-and-sustainable-clothing-brands-from-au-and-nz/

Rauturier. 2021. Good on You. What is Fast Fashion. https://goodonyou.eco/what-is-fast-fashion/

Sustain Your Style. 2020. What’s wrong with our fashion industry. How can we reduce our Fashion Environmental Impact? https://www.sustainyourstyle.org/en/reducing-our-impact

Target. 2021. Target Australia. Sustainability and Community. https://www.target.com.au/company/better-together/people/human-rights/traceability-and-transparency

Weavabel. 2021. Weavabel.com. Fast Fashion and Sustainability: Will the two ever get along? https://blog.weavabel.com/fast-fashion-and-sustainability-will-the-two-ever-get-along

Zhou, M. 2021. Refinery 29. It is possible to buy fast fashion more sustainably- here’s how. https://www.refinery29.com/en-au/sustainable-fast-fashion