A Friend Called Pain.

AS I went to ask my first question I heard a crunching of bones as Robbie moved his foot back and forth. A grimace. And then a wry smile. What was that? I ask. “Sometimes, a loose piece of bone breaks off and I have to dislodge it to ease the pain.”

Robbie Partridge is 41. Six years ago, in a drunken incident, he jumped off the second story of the Pineapple Hotel to help a mate in a fight down on the street.

“It was the Mundine, Green fight. Everyone was pissed up, revved up and I tried to land the jump on the back of a ute. It didn’t come off.”

He laughs at this, triggering a hesitant accompaniment by myself.

“I went to the doctor the next day but he told me it was just a ligament strain. A few days later, after it had blown up, I went to the hospital. The main diagnosis was that I had a compound fracture through the ball joint of my right heel.”

Speaking to Doctor Ben Forster, an orthopaedic surgeon at the Mater, he described this injury as “…the fracturing of bones where it opens the skin. Robbie’s ankle was also broken and now he’s left with a foot that has a lot of fragmented bone floating around and calcified cartilage.”

I watch as Robbie pops a wheelie in his wheelchair, and rolls forward with ease. I’ve come here to ask about the debilitating nature of chronic pain. The way it derails peoples mental health and presents a life of physical and emotional struggle. It seems as though I’ve chosen the wrong interviewee.

“There’s not much point in feeling sorry for myself. I went through that. I was depressed, suicidal. Living with Mum and Dad in your 30’s wondering if you’ll ever walk again is nothing good for your head.”

Robbie can walk, in excruciating pain. There is a pair of crutches by his front door, and walking sticks lay against the walls of his apartment. These, so far, the most obvious signs of the pain he lives with everyday. During the interview, I watch him grab one of his sticks. He steady’s himself, rises from the wheelchair carefully and stands still. Then, a slow limp to the fridge where he points out a photo of him in Japan.

“I was always on the move. I lived overseas a lot, working, partying. The hardest thing about this has been how it’s stopped me in my tracks. I’ve never been forced to slow down before.”

But what of the pain, that seems so far from his mind?

pain“It’s always there. I try not to talk about it too much, try to remove the focus. If I had to describe it for you, it’d be like my base pain is 70% of the pain when you break a bone.”

Having broken my leg a couple of times, this statement floors me. How is he carrying on a conversation with me with pain levels like that?

Doctor Coralie Wales, President of Chronic Pain Australia, described Robbie’s ability to detract focus from his pain as the control stage.

“It’s a process, being able to find how to manage or control chronic pain. It’s so hard for people who do not suffer with this to truly comprehend the 24/7, every waking moment nature of chronic pain.”

Chronic Pain Australia is an organisation that seeks to provide a community of support for those who suffer.

“Although the cause is varied for all sufferers,” Dr Wales says, “I often here people say there is an understanding between people in pain that is not quite there with others, even from family members, who are often their primary carers.”

And what of the loved ones who take on a secondary role as carer? Dr Wales had put me in contact with a young woman, Jasmine, whose mother suffered from a back injury that had enveloped her in the world of chronic pain.

“We’re family, so I don’t feel sorry for myself, like being there for my Mum is a cross to bear. I mostly hate the way it’s changed her view on life.”

Speaking to Jasmine’s Mum, Diana, I ask her how she feels about the pain.

“It’s awful, I have to sit or lie in one position. I can’t do anything anymore. I won’t get into a wheelchair because I feel like that’s giving up.”

I picture Robbie, and how mobile his wheelchair made him and I begin to see that chronic pain is universally a physical struggle. But the mental way people deal with it is an individual battle… how people cope is personal and behind closed doors, the two women’s eyes tell me it is gut-wrenching.

At one point, I try to encourage Diana, saying her daughter is young and she has grandchildren yet to look forward to.

“I’m not that young,” says Jasmine. She is 22.

I have been shocked at the effect of chronic pain on Jasmine, distorting her view on being aged. It should have been obvious, but strangely I felt I had been totally ignorant of the reverberating effects of chronic pain on all those involved.

“Mate, pain is ongoing,” Robbie said to me during our interview. “At some point you make a choice to keep living, or, feel sorry for yourself. And I can tell you one is easier than the other. But not necessarily better. It’s much more mental than physical.”

Dr Wales had mentioned this, saying chronic pain is oft thought to be a solely physical battle.

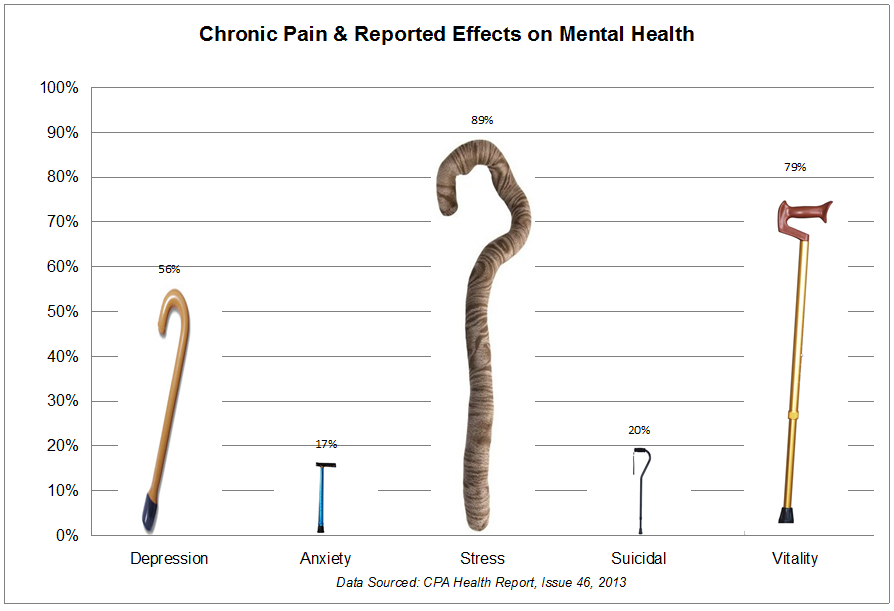

“But organisations like ours heavily focus on creating an environment of support for the huge emotional and mental obstacles sufferers face. This is what can make the difference between coping with the physical aspect or not.”

I had been confused by the contrast in attitude between Robbie and Diana at first. And as I continued to ask questions my story seemed further from a fitting end. What had I endeavoured to conclude when I began to write this story? Weren’t they both suffering from the same affliction? As far as I could tell, the only parallel was the physical pain.

“It’s good that you’re giving a silent monster a voice,” Robbie told me.

“And that there is no clear-cut way to cope, no end date, is the honest way to write this story. You told me this was about human tragedy but I reckon you’ve also written a story on human triumph. Pain is weakness leaving the body.”