For sale: Brides

MY AN is a happy two year-old who spends most of her time laughing, playing and enjoying life in the remote, northern Vietnamese village of Y Linh Ho. She is still unaware of the dangers she faces as a young girl in one of the world’s human trafficking hotspots.

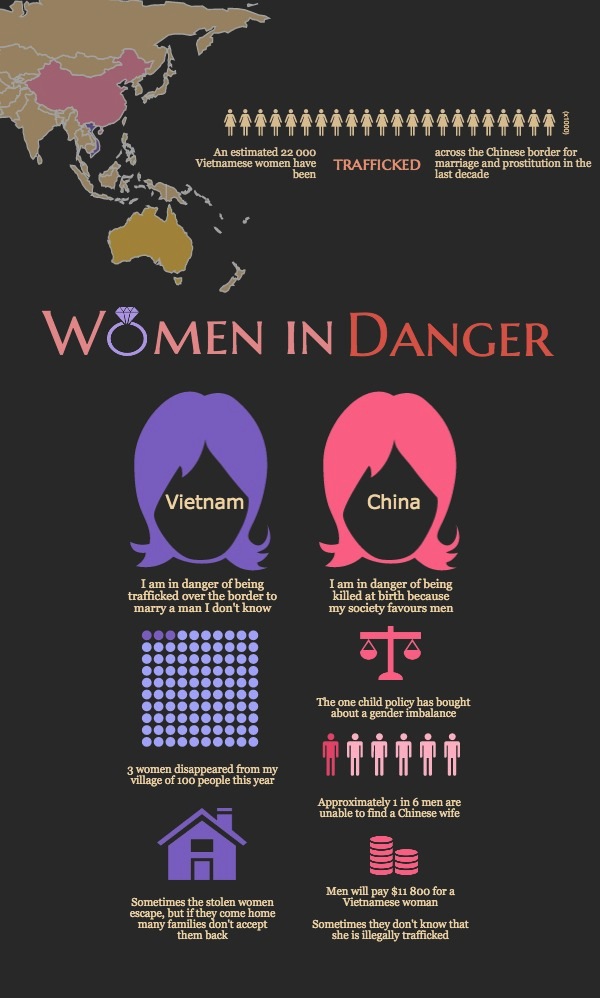

Every year, about three women disappear from her tribal Hmong community of barely 100 people– and her village isn’t the only one. In the last 10 years more than 22,000 Vietnamese women have been trafficked across the border to marry Chinese men whom they’ve never met.

The underlying issue being that China, Asia’s most populated country, has too many men and they’re on the hunt for a wife.

China’s National Bureau of Statistics reports that there were 33.8 million more men than women in China during 2013; a number that the Global Black Market information provider, Havoscope, relates directly to the trafficking of neighbouring Vietnamese brides.

“Security experts in both countries [China and Vietnam] state that the gender imbalance in China is leading to more women from neighbouring countries to be trafficked. With 33.8 million more men in the country, many men in rural areas are finding it difficult to find available women, leading to the black market in brides,” says a Havoscope spokesperson.

With her biggest challenge being conquering the nappy era, the last thing on My An’s mind is boys – especially marrying one. Nevertheless, all too soon she will be old enough to sell hand-made goods on tourist-laden streets, exposed to the prying eyes of bride traffickers.

Where the Hmong women used to trade in Sapa, a tourist township in rural Vietnam, new laws have prevented them from doing so, in turn forcing them to stick to the common tourist routes, resulting in many receiving a negative wrap from visitors.

Brianna Piazza was touring in Vietnam when she first came across the Hmong women and it wasn’t until her tour guide, Zi, informed her of the women’s situation that she became empathetic.

“On the last night of our trip we told Zi that we weren’t happy with the women following us all day and said the tour would be much more enjoyable if they weren’t there,” Brianna said.

“The women literally followed us up and down the mountains, through the mud, with babies on their backs and some even stayed close during our meals. Zi [tour guide] told us the reason why the women followed us the way they did throughout the trek was because the government was cracking down on illegal street trade and this was one of the few options available to the poor women to earn some money for their families.

So to avoid getting caught and avoid beatings from police for illegally selling souvenirs to tourists on the street these women followed tourists on the treks through the valleys and up the mountains. It’s safer there for them. She also said women frequently get abducted from the villages just outside of the Sapa township,” she said.

“Zi said that in her small village alone, around three young women or girls are abducted each year. They somehow know that the women are taken over the mountains into China by traffickers and are often forced to become a Chinese man’s bride.”

My An’s parents, tour guides Sinh Le Loi and Ly May Giang, know of several families whose women haven’t come home from work one day and grimly acknowledge how the traffickers have tricked them.

“They [traffickers] say that the girl’s husband is no good and he just drinks all day. That if they travel over the border and marry another man their life will be pure happiness,” said Sinh.

What he describes isn’t uncommon and researchers at the Global Freedom Center confirm that vulnerable women in remote communities are manipulated, abused, and constrained by their traffickers.

“Traffickers use dehumanising tactics to compel such as physical force, psychological coercion, threats and outright fraud,” a representative of the Global Freedom Center said in a prepared statement.

“Psychological coercion has proven to be just as powerful, if not more powerful, than physical force, creating invisible barriers to a trafficked person’s escape.”

“This includes confiscation of immigration an identification documents coupled with threats of jail and deportation, threats of harm to trafficked persons and their family members, and threats to tell family members and community that the sex trafficked person is in prostitution, which would bring shame.

“Traffickers play mind games by suggesting that the compelled service [trafficked person] violates criminal and immigration laws, making trafficked persons think they are criminals and fear law enforcement, effectively blocking law enforcement as a resource.”

My An’s mother, Ly May, says that rural Vietnamese women often leave willingly in the hope of living a better life.

“Before it used to be a problem where people were getting kidnapped, but nowadays people are willingly going to China to find a better life. Many know that they can easily find someone who will sell them into this better life,” Ly May said.

As Carolyn Kitto, Australia’s Stop the Traffik coordinator, says, once a woman has packed her bags and been taken away, the situation she finds herself in is not the ‘better life’ she expected.

“Every situation is different – but in common – they are deceived or coerced or tricked. They are exploited in a range of ways (physical, emotional and sexual) and someone benefits from the process,” Carolyn said.

However, perhaps the most frightening part is that the trafficked women are often not welcomed back if they ever return.

Sinh recalls how other women have come home to a family that is essentially disgraced and embarrassed.

“People around women who return home speak about her a lot. They say that she has been stolen by someone and used for sex. Many don’t like the women who are trafficked,” Sinh said.

For now, the most important task for Sinh and Ly is keeping their daughter safe. Sinh stresses the importance of teaching My An that people are not always what they may seem.

“I just tell her [My An] not to believe the people too much, because we know people but we don’t always know what they’re thinking,” Sinh said.

Beyond this, all he can do is hope that his family do not become another statistic in human trafficking.

“I feel scared,” he said.

This post was originally published on Golden-I UQ 2014.