Gayndah is Finished

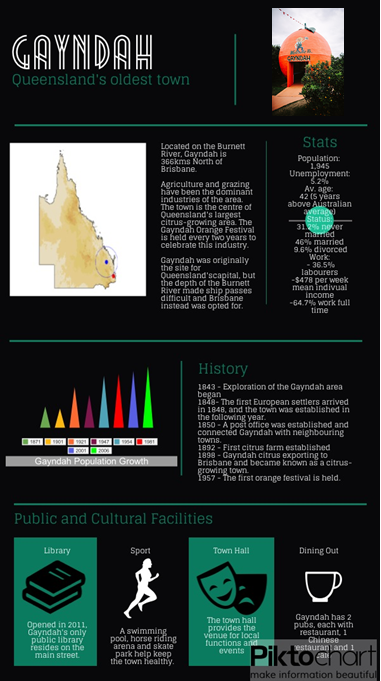

IT’S 5.15pm and one of the two pubs in the rural Queensland town of Gayndah, 366kms north-west of Brisbane, is quickly filling up. One-by-one, customers trickle into The Grand Hotel.

They all know each other and the mood is nothing but friendly. As the afternoon wanes, the draughts, ales, malts and other social lubricants ensure voices become louder, language cruder, laughter more frequent and acquaintances again become dear friends. The reality of life in this small, isolated town can, at least temporarily, be ignored.

Today is Tuesday. The working week has scarcely begun, but the regulars are all here. It has taken just four visits to learn their names, seats, drink of choice and how without a single word a beer can be ordered, paid for and served.

The Grand has 22 ‘everyweekers,’ the ‘com-ers and go-ers,’ who appear after a particularly rough day on the farm. Publican Rodney Vickers says these are the ones to watch, drinking too much, too quickly and seeking a quick fix for whatever has troubled them on that day. There are the 42 ‘weekenders,’ flocking to the bar on Friday and Saturdays, many with partners and families they leave at home. Tonight it’s the 6 ‘everydayers,’ the pride and joy of bartenders that take ‘their’ seats in ‘their’ bar, having their drinks poured exactly the ways they want, who are creating the ambience. Each will spend at least $20 a night during the week and $50-100 on weekend binges.

Seated nearby is 67-year-old widow, Thelly. Her daughter recently moved to America but Thelly has no desire to leave Gayndah and doesn’t believe she’ll ever see her girl again. Thelly likes her VB in a bottle because it tastes better and she has cattle dog called Oscar who waits patiently outside. When asked why she and the other five ‘everydayers’ come here, her reply is quick.

“Loneliness,” she says. And then, “and beer, of course.”

She lives alone and finds some aspects difficult, but insists she’s okay. She comes to The Grand because she knows there’ll always be someone here who will listen to her.

“The alcohol takes off the edge,” she says. “It doesn’t matter what we’re talking about if we’ve all got stubbies.”

Like Thelly, John has been here the past four nights, each time drinking himself into a stupor before saluting the bartenders and disappearing. But he’s more of a listener. At 10.30pm and on his eighth schooner, he pipes up briefly to say he “may as well live here”.

Five years ago, John was in a car accident with three of his best friends and the previous, beloved publican. Driving him home, they hit a tree. John was the sole survivor. Since then, his wife and three kids have left him and Gayndah behind.

“This is how I remember them,” he says, the corners of his mouth smiling, but sadness showing in his alcohol-hazed eyes. With a cheeky wink and a glass-raise at the barmaid he continues. “I love this place, I’m always looked after.”

“This is how I remember them,” he says, the corners of his mouth smiling, but sadness showing in his alcohol-hazed eyes. With a cheeky wink and a glass-raise at the barmaid he continues. “I love this place, I’m always looked after.”

Barmaid Narelle Emerson has worked at The Grand for 10 years and seen the comings and goings of the regulars. To her, The Grand is not just a place of employment. It’s where those who don’t have anywhere else to be, go. It’s a bolt-hole the locals use to escape the rural isolation, the hard-work and societal problems that come with it.

“I’m the bartender, but I’m the psychologist too, “ Narelle laughs. She humors her customers and cares for them. Always moving, she shakes a finger slyly at one man’s inappropriate joke, brushes the dust off an old bottle of port, picks the cheapest cask wine for two young, non-English speaking fruit pickers, and asks upholds several conversations at once. She says every night someone comes for the sole purpose to get ‘blind’. But a good bartender knows not to judge.

During a tour of the near-deserted main street, life-long Gayndah resident, Councillor Jo Dowling, points out the swimming pool and events hall, but recognizes that there is very little else to do or spend money on in the town, which has encouraged the drinking culture.

“People don’t want to be bored and alone,” she says. “That’s the reality for so many here. With each house being so far apart and the town itself being so far away – it’s like living in a dome. It isn’t common for people to leave or move here, so a lot of Gayndah is generational and cyclic.”

Gayndah is one of many rural towns where the drinking culture, due to isolation, loneliness and boredom, is prevalent. As farmers and rural communities struggle with harsh environmental and economic circumstances, it’s the very stoicism, strength of character and self-reliance integral to life on the land that can allow depression and anxiety to fester and grow. Famers take pride in their independence and ability to overcome adversity. The nature and location of farm and rural work often demands self-reliance and the detrimental effects of alcohol-related harms are preferable to the harms related to loneliness and isolation.

Gayndah 5According to the National Rural Health Alliance, those who live in rural and remote areas are 32 per cent more likely to drink at levels that risk causing lifetime harm and 24 per cent more likely to drink at levels that are at risk of resulting in single-occasion harm than those living in urban areas.

“People don’t want to be bored and alone,” she says. “That’s the reality for so many here. With each house being so far apart and the town itself being so far away – it’s like living in a dome. It isn’t common for people to leave or move here, so a lot of Gayndah is generational and cyclic.”

Gayndah is one of many rural towns where the drinking culture, due to isolation, loneliness and boredom, is prevalent. As farmers and rural communities struggle with harsh environmental and economic circumstances, it’s the very stoicism, strength of character and self-reliance integral to life on the land that can allow depression and anxiety to fester and grow. Famers take pride in their independence and ability to overcome adversity. The nature and location of farm and rural work often demands self-reliance and the detrimental effects of alcohol-related harms are preferable to the harms related to loneliness and isolation.

According to the National Rural Health Alliance, those who live in rural and remote areas are 32 per cent more likely to drink at levels that risk causing lifetime harm and 24 per cent more likely to drink at levels that are at risk of resulting in single-occasion harm than those living in urban areas.

Publican Rodney Vickers is committed to preventing the reputation of rural pubs being tarnished.

“A lot of pubs cop a lot of flack for what they harbor,” he says, “but I think this is just a way for people to be looked after. This is, at the end of it all, a happy place.”

It is 12:35 and one of the two pubs in the rural Queensland town of Gayndah, is quickly emptying. Mr. Vickers is asking his final customers to leave the pub, ushering them out and locking the door before curfew.

“Come on now, mate,” he says. “It’s time to go home.”

But there are no hard feelings here; they’ll be back tomorrow, same time, same place. That’s just the way it is.