The fence that could save Queensland’s wool industry

Story by Courtney Lawler

STRONG fences make for good neighbours in the suburbs. In the west, they are all that stand between farmers and financial ruin.

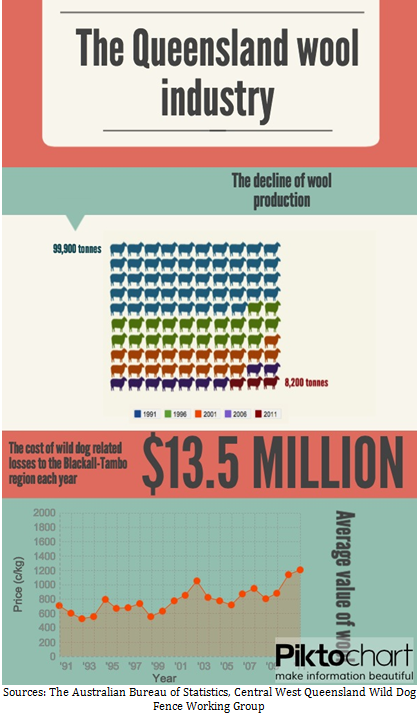

Wild dog attacks cost sheep producers in the Blackall-Tambo region of Western Queensland an estimated $13.5 million each year in livestock losses, trapping and baiting.

Ironically, the same amount of money could build a proposed 1600km fence to protect the state’s prime sheep country.

But it’s not that simple, because in farming, nothing ever is.

Wool production has been steadily falling for years in Queensland, dropping from 99,900 tonnes in 1991 to 8200 tonnes in 2011.

A recent study commissioned by the State Government revealed graziers in the Blackall-Tambo region consider wild dogs – domestic canines that have interbred with native Dingoes, and are classed as feral pests – to be one of the key causes of the decline of the sheep industry.

Little wonder then that hunters shoot and scalp the dogs, and string them up in trees.

Blackall fencer Douglas Atkinson said, “Things are getting worse every year”.

Mr Atkinson, who has been running cattle and a commercial fencing business in Blackall for 40 years, has recently experienced a boost in business due to increased demand for vermin fencing.

Lawler 2“Five years ago, we didn’t have a dog problem,” says Mr Atkinson.

But with baiting and trapping proving ineffective against the rising wild dog population graziers are being forced to fence enclosures on their properties to ensure “safe zones” for their flocks.

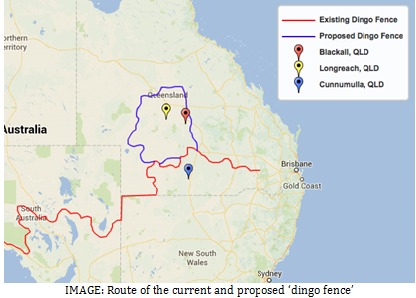

Made from the same material as the 2500km ‘dingo fence’, that runs from the Darling Downs to the Eyre Peninsula, vermin fencing is specially designed to ensure that wild dogs cannot penetrate it.

Priced at about $7000 per kilometre, vermin fencing is expensive for graziers.

Though Mr Atkinson says local producers have crunched the numbers and have decided it is well worth the cost.

“Fencing gives them some reassurance that they can stay in the industry, otherwise I don’t know what you do…you’ve gotta survive somehow.”

Graziers who have invested in fenced enclosures are now marking 95 to 100 per cent of lambs, as opposed to graziers without enclosures who are only marking 30 to 40 per cent, or, in extreme cases, zero.

Several graziers have reported losing up to 70 lambs in a night to packs of wild dogs, amounting to a loss of up to $35,000.

“That happens to people every night,” says Mr Atkinson.

There are calls from many wool producers in Queensland’s central-west to build on the success of vermin fencing and erect another wild dog fence.

Lawler 3The proposed fence would begin and end at the existing fence, but would encircle the wool producing shires of Blackall-Tambo, Longreach and Barcaldine.

It has become increasingly clear to wool producers like Jenny Keogh that the current wild dog control methods of baiting and trapping are simply not working.

Ms Keogh, the chairperson of the Leading Sheep advisory panel, says that a collaborative approach to dog control, using baiting, trapping, and fencing, is essential.

“We have to utilise every tool available to us…we have to change the game, or the region will just die.”

As wool production has decreased in the Blackall-Tambo region, so has the population.

In it’s hey day, Blackall had 5000 residents; now there are about 1200.

“We’ve lost our shearing groups because there wasn’t enough work, which means that people move away, which means that the schools lose children, and the population continues to decline, “said Ms Keogh.

A recently completed feasibility study funded by the Queensland Government has predicted that the proposed multi-shire fence would cost approximately $13 million to erect.

The report also predicted that the economic benefit of the project would be upwards of $6 million in the first year, with benefits increasing as the wild dog population is brought under control.

With the feasibility study completed, the next step for Ms Keogh and her colleagues is to present the findings to the State Government and explore joint funding models.

“As with everything, finding money is difficult,” says Ms Keogh.

“But what heartens me about this project is that it will provide a return to the whole region, not just the wool producers”.

However, the proposed wild dog fence is not without opposition.

Environmental organisations such as Wildlife Queensland have raised concerns about the impact of a fence on native flora and fauna, and some Blackall residents question the practicality of the fence.

Blackall-Tambo Councillor Jeremy Barron says, “The [dog] problem is massive.”

“ It’s destroyed the wool industry in Blackall.”

A key member of the Blackall-Tambo Wild Dog Advisory Committee, Cr Barron sees the destruction and heartbreak caused by wild dogs on a daily basis. Yet he remains sceptical about the proposed fence.

“The problem with a fence is that you’re always going to have people on the inside and people on the outside.”

“You’ll always be fencing people out,” says Cr Barron.

He says that a more viable strategy would be for syndicates of graziers to pool their resources and fence large “islands of safe property,” rather than paying for a fence to protect an area that will also include properties which run cattle or grow crops.

Both strategies have their merits, and most agree that what is needed is a coordinated, collaborative approach.

Until then, the losses will go on, farmers will go under, and the industry will continue to suffer.