Toll paid for gift of life

IT’S 3am Sunday as a third patient gets wheeled into the operating theatre at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital.

The night had been particularly difficult for scrub nurse Annie James, a 25-year veteran of organ donor retrievals; all three donors were 19, the same age as Ms James’ two children.

“It was one of those nights that followed the rule: see one, see three,” she said.

Organ donation is medically possible in less than one percent of all deaths that occur, but for Ms James, the potential cases always seem to come.

The process that follows is lengthy. And though Ms James is guided by sure knowledge each donor could save up to 10 lives, here she admits to something many might find shocking.

“You feel so incredibly sad for these people, and knowing what the process is like, I just don’t know if I would be a donor myself,” she said.

Donor and recipient families are not exposed to the intricacies of the retrieval surgery, but these operations, often performed late into the nightshift, can have a profound and lasting impact on many scrub and theatre nurses.

“We only see the dead body and the aftermath: the traumatic part,” Ms James said.

“It’s just awful, they cut them from the neck to the pelvic bone and it’s an open field.”

“We never get to see the other side with a kid waking up for the first time with a beating heart. We’re always left with that empty feeling.”

Nurse Emily Carmichael is relatively new to the organ retrieval process but already grapples with conflicting emotions.

“I find it frustrating that we only see one piece of the puzzle at RBWH,” she said.

“It’s often made harder by the fact that most organ donations are from relatively young and fit patients. After these surgeries my ‘problems’ seem so irrelevant.”

Nurse Alexa Chadwick copes with donation by putting “a personality to the patient you’ll never get to talk to.”

“I have to remind myself that they’re a human being, not a science experiment and they have made such a wonderful choice, so I want to do my best for them,” she said.

If anything it makes me appreciate what I have, because there are so many people who spend their lives in and out of hospitals due to organ failure. To think that the decision of one person can change so many people’s lives is just phenomenal.”

Bianca Topp, Donation Coordinator at the Princess Alexandra Hospital, is driven by those who put their grief aside to think of others in desperate need of transplants.

Bianca Topp, Donation Coordinator at the Princess Alexandra Hospital, is driven by those who put their grief aside to think of others in desperate need of transplants.

“Even though I’m exhausted after the surgery, I feel incredibly proud of the patient because they have chosen to save someone’s life,” she said.

Since 2005, Queenslanders have been unable to register their donation wishes on their driver’s license, ultimately leaving families with the decision to give the “final ok.”

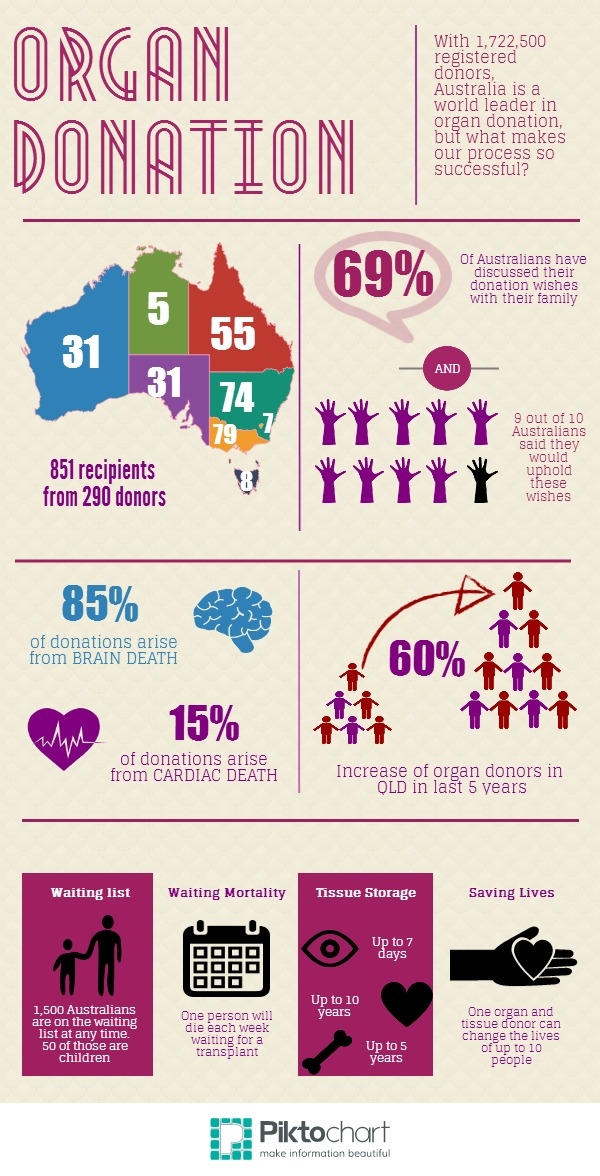

According to the Australian and New Zealand Organ Donor Registry, in 2014, 851 people received organ transplants as a result of 290 organ donors whose families agreed to donation at the time of their death.

Although three in four Australians have discussed the subject with family members, only 53-percent of people reported knowing their loved ones’ donation wishes.

It is rare that the family does withhold permission, but it does happen.

“It’s a very disappointing situation to come across and it’s usually because the deceased and their family have not had an open and frank discussion about donation,” Ms Topp said.

Theatre nurse Belinda Johnston acknowledged the complexity of giving consent.

“Organ donation is a very harsh, gruesome and rushed operation, and is especially difficult when it involves a relative. Often the fear about the retrieval process and the tight time constraints make the decision to consent very difficult,” Ms Johnston said.

The stringent testing conducted by the Australian Organ and Tissue Authority, to match donors and recipients, is another contributing factor in Australia’s high transplantation success rates.

As Donate Life Queensland report, since 1965, more than 40,000 Australians have received life-saving organ and tissue transplants.

Professor Jeremy Chapman, the world’s leading expert in kidney transplantation, attributes this success to drastic improvements in diagnostic techniques and drug development.

“We’re fantastically lucky to have such a good donation system in Australia. People are dying (elsewhere) for a lack of the systems we take for granted,” he said.

These solid systems have generated incredible progress.

“When I started in the field, 36 years ago, the survival rate for a young adult with kidney failure was 50-percent, now it is around 98-percent,” Professor Chapman said.

And with these continued improvements come huge possibilities for the future of organ donation.

Professor Chapman envisions a not too distant future where, “there is a possibility we could repair a damaged kidney without the need for a transplant.”

However, with more than 1,500 people on the transplant waiting list at any time, Professor Chapman emphasised the importance of normalising the concept of organ donation.

“If you die and your organ is suitable for donation, your family should expect to be asked. It’s nothing special, it’s very normal,” he said.

“On another level it is special. You’re giving someone a new life. However, as physicians, we must never take for granted the view that someone should donate, once suitable.”

Ms James still struggles with her own donation wishes and dreads seeing a donation on the theatre schedule, but finds solace in that patients are always treated with dignity.

“In Australia, all aspects of the process are done tastefully, with respect and sophistication. Our approach has obviously contributed to the outstanding progress Australia has made in transplant medicine,” she said.

But real comfort only comes from what she says is the most rewarding part of the process – receiving a letter from Donate Life, which details the outcomes of each donation.

“It’s such a vital surgery and to know the outcome reinforces the reason why I scrub in every day,” she said.

“While it’s the end of someone’s life, it’s also the beginning of another.”

To register your donation decision, go to www.donorregister.gov.au

This post was originally published on Golden-I UQ 2014.