What Are You Going To Do About It?

There are over 7,980,666 different people, 195 different countries, and 6,500 different languages in the world, yet we all have something in common (Worldometer, 2022). We live on the same Earth, and it’s dying.

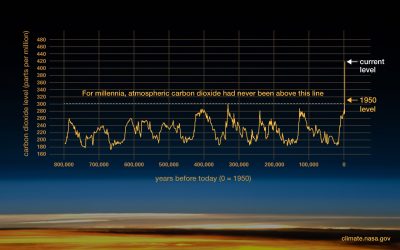

Source: https://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/

According to NASA, human activities since the 1800s have warmed the Earth at a rate never seen before (2022). Earth’s temperature has risen by 2 degrees Celsius due to skyrocketing atmospheric cardon dioxide levels, so our ice sheets are shrinking, glaciers are retreating, sea levels are rising, ocean acidification is increasing, and extreme weather events are occurring more frequently than ever before (NASA, 2022).

The United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) act as an urgent call for action for all countries to work together to protect our Earth and the people who live on it (United Nations SDGs, 2022). As its name suggests, sustainability is at the very core of the SDGS. From Goal 13: Climate Action, to Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities and Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, it’s quite clear that everyone, everywhere, should be working towards more sustainable practices to save our home.

Unfortunately, it’s much easier said than done. Although we live on the same Earth, our cultural, social, economic, and political priorities are incredibly different, let alone our available resources.

Picture this: you wake up and wiggle as silently as you can between your family members, who lay asleep on the floor of the single room you’ve always shared. As you get older, the walls are squeezing in. You pull your yellow uniform over your head and get a passing whiff of its salty, tangy odour, which always grows stronger towards the end of the week before mum does the handwash. Your shoes feel comfortable but squishy, and your big toe is starting to poke out on the left foot.

You stuff your notebook and pencil into your backpack and gently tuck 10 rand into the little zipper pocket at the front. The coins jingle together as you swing the backpack over your shoulders.

Mzabalazo Primary School is three kilometres away, so you start walking.

Hours of classes pass, and a low grumbling feeling begins echoing through your limbs, so you’re excited when the lunch bell finally chimes. There’s a discarded, empty plastic milk bottle on the ground that you kick to your friends as you race to the nearest canteen. It’s not as good as a soccer ball, but it does the trick.

Your group beats the crowds for once and you smile, quickly pulling out your tiny handful of coins before any of the older kids can push in. 10 rand is just enough to give you some options but rules out what you really want – hot chips. Luckily Mrs Achebe will be handing out rice as she always does at lunch time. Your stomach rumbles again. “One Coke please.”

Once the rice and soft drink settle in your stomach and the grumbling eases, you drop the plastic Coke bottle on the ground and kick the milk bottle to a more spacious dirt area near the canteen, where you and your friends play soccer for a while until a white minibus pulls up. Tall people with light-coloured skin step out. There are so many of them! They all hold up their phones and tap the screens. You don’t know who they are, but they clearly aren’t from here.

You pause with the milk carton under your foot and catch your breath, watching them walk towards the canteen. One girl with a fluffy yellow ponytail pulls out hundreds of rand from a shiny black wallet and flips through them before choosing one and handing it over to Imani, the canteen man, who passes a Styrofoam container through the little window. You close your eyes and breath in the salty, oily goodness.

The tall white people are in your final class of the day – Maths – but you can’t focus on what they’re saying because you’re transfixed by dozens of pairs of unbelievably white shoes. You wiggle your left big toe and it pops in and out of the hole, bigger now after playing soccer.

Your stomach grumbles again so you cross your fingers under the desk – hopefully Mamma has saved enough rand this week for a special KFC dinner. After noticing the discarded packaging on the side of the road this morning, you’ve been craving it all day.

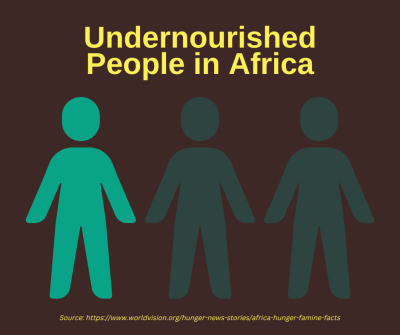

This little boy’s cultural, social, economic, and political priorities are different to those of first-world individuals like you or me. How can sustainability be his priority when the simple act of having food to eat is more important than the type of food, or the way that food has been produced or wrapped? In Africa, over 282 million people – one third of the population – are undernourished (World Vision, 2022). Sustainability won’t matter to this little boy as much as filling his stomach will.

On the other hand, 90% of Australian consumers and businesses are concerned about environmental sustainability (Taylor, 2018). Our governments, businesses, communities, and individuals have collectively poured resources into improving sustainable practices and, as a result, Australia’s Environmental Condition Score improved from an extreme low of 3.2 in 2020 to 6.9 in 2021 (TERN, 2022). We are privileged that sustainability can be one of our priorities.

When I visited St Lucia in South Africa, I learnt the country’s monster coal industry ranked it as one of the world’s top 20 emitters of greenhouse gas (OECD, 2013). I was also stunned by the lack of fresh food and abundance of plastic and litter that lined the streets, which went unnoticed at schools and poured from the few rubbish bins available.

I asked Cass, a new Canadian friend who had lived in St Lucia for over six months, what she thought. Cass said,

“I don’t feel it’s right to go into the village and say to a family who don’t have food ‘oh I’m sorry you shouldn’t use plastic,’ because that’s coming from a place of extreme privilege as we’ve grown up somewhere where food is fresh and not wrapped in plastic.”

People from Western countries, like you, me, or Cass, would have picked up the plastic milk carton and put it in a bin before thinking to play soccer with it. Rather than dropping an empty Coke bottle on the ground, we would have searched for a recycle bin. We also would have expected our hot chips to be served in biodegradable cardboard packaging instead of Styrofoam, which is not environmentally friendly.

To this little boy, discarded rubbish is a soccer ball and plastic-wrapped food is still food. We have different approaches to our shared problems.

However, a local St Lucia woman named Zine didn’t see sustainability as a privilege; she saw sustainability as a necessity. After all, how will her people fight bigger demons, like famine, when they don’t prioritise caring for the very thing that will prevent famine in the first place – our Earth? Zine said,

“In Africa it’s important for the ground because if it’s covered in litter, we cannot grow any plants for vegetables in the proper way.”

Unfortunately, this is an excruciating cycle that begs the question – did the chicken or the egg come first? Unsustainable habits prevent the growth of good crops, which tips Africa further into famine and therefore further away from achieving SDG Two: Zero Hunger. Breaking those habits can only be achieved by reducing plastic food waste, but reducing plastic food waste can only be achieved by growing good crops. Zine said,

“When kids eat chips, they will chuck the packet on the ground. Even though the schoolteachers try and tell them to pick up their litter after break, the kids aren’t told why it’s important to not chuck their garbage on the ground, so they don’t stop.”

Meanwhile, Australian children are actively being educated on more sustainable ways of living because it’s a compulsory cross-curriculum priority (Australian Curriculum, 2022). Since 2018, plastic straws have been banned, Queensland has planned to build the largest publicly owned wind farm, water efficiency in the cotton industry has improved by 40%, Sydney hosted the first sustainability-focused fashion show, Australia Post saved over 17,000 tonnes of carbon, and more than $500 million has been invested in protecting the Great Barrier Reef (Australian Government, 2018). This only scrapes the surface.

You and I are different to this little boy. Our cultural, social, economic, and political priorities are different, and so the way we approach sustainability is also different. Perhaps burning litter on the side of the road is the most effective way for you to be sustainable, or perhaps it’s reducing your meat intake. Perhaps it’s about education, or perhaps it’s about motivation. Perhaps you’re trying to fight the coal industry, or perhaps you’re trying to remember your Keep Cup.

Regardless of the form sustainability may take for you, me, or this little boy, it is always important. We are equally powerful in our different contexts, and using our power is what will make a difference.

So, what are you going to do about it?

References

Australian Curriculum. Sustainability (Version 8.4). (2022). Retrieved 8 October 2022, from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/cross-curriculum-priorities/sustainability/

Australian Government. (2018). Report On The Implementation Of The Sustainable Development Goals. Australian Capital Territory. Retrieved from https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/sdg-voluntary-national-review.pdf

NASA. EVIDENCE: How Do We Know Climate Change Is Real?. (2022). Retrieved 5 October 2022, from https://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/

OECD. South Africa shows good progress on environment, must keep up pace. (2013). Retrieved 6 October 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/south-africa-shows-good-progress-on-environment-must-keep-up-pace.htm

Taylor, L. (2018). New Research Sheds Light On Australian Attitudes Towards Environmental Sustainability. Retrieved 6 October 2022, from https://planetark.org/newsroom/archive/2533

TERN. (2022). Australia’s Environment in 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2022, from https://www.tern.org.au/news-australias-environment-in-2021

United Nations. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. (2022). Retrieved 9 October 2022, from https://sdgs.un.org/

Worldometer. World Statistics. (2022). Retrieved 8 October 2022, from https://www.worldometers.info/

World Vision. (2022). Africa Hunger, Famine: Facts, FAQs, and How To Help. https://www.worldvision.org/hunger-news-stories/africa-hunger-famine-facts. Retrieved 6 October 2022, from https://www.worldvision.org/hunger-news-stories/africa-hunger-famine-facts