Why is it so hard to ‘eat local’ when it comes to seafood?

Next time you are browsing the seafood section of your local supermarket, take a minute to think about this: more than 70% of seafood consumed in Australia, is imported.

So – why is this happening? And if not here, where is the seafood coming from?

With a rising population and increased regulation to fishing practices, Australian fisheries and aquaculture industries are finding they are unable to produce enough stock to meet demand.

Although reduced fishing effort and increased management contributes to the sustainability of fisheries, Professor Anthony Richardson says “it opens the way for a lot of imports.”

“It’s all part of the bigger picture of why there is a demand for imported seafood,” he said.

“Our production costs here for prawns, for example, would be around $12 per kilo, whereas, if you were farming in Ecuador, if you weren’t below $5 per kilo you wouldn’t be in business”

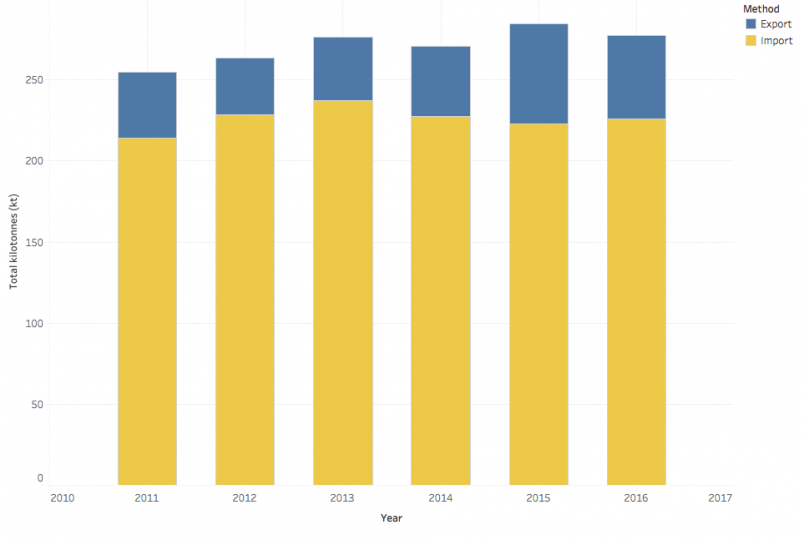

^ Total kilotonnes (kt) of seafood from import and export industries in Australia from 2011 – 2016

As part of their “Fish, Fisheries and Aquaculture” course, students from The University of Queensland were asked to find out what they could about the seafood available from their local supermarket.

In response to consumer demand for clear and meaningful origin labels on food, new labelling laws were introduced in July 2016.

Under Australian Consumer Law, the new labels should describe not only the country of origin but also list the location in which it was packed.

Although not yet mandatory, the students found the country of origin labels were not common. Despite this, they did find that some of the products were travelling astonishing distances to reach our shelves.

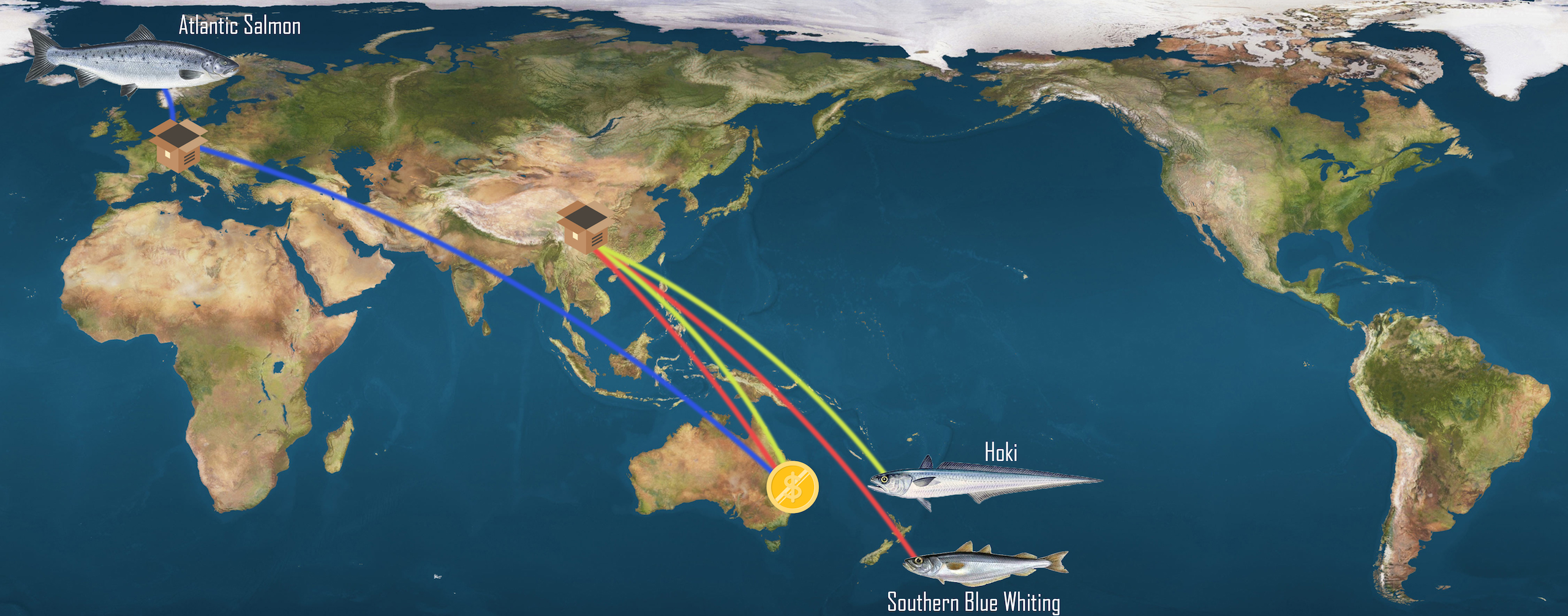

With Atlantic salmon farms on our doorstep in Tasmania and off the coast of New Zealand, the students found plenty of salmon had instead come from Norway and been packed in Poland before being sent to Australia.

In the local supermarket or even at your local monger, it is very likely you will find fillets of Barramundi, an iconic Australian fish, on offer. Typically sourced from Vietnam, it will most likely have been farmed and frozen before reaching Australia.

Many Australian’s eat Atlantic Salmon at least once a week, making it a popular choice. However, if farmed in New Zealand, students found it was typically sent to China for packing before it arrived in Australia to be sold.

Director of the Centre for Marine Science at The University of Queensland and Associate Professor Ian Tibbetts received a similar shock recently when preparing a meal for his grandchildren.

“This [packet of fish] was European cod. It had come from the Atlantic ocean, half a world away.”

“Not only that – it had been via China on its way to the freezer from where I bought it,” he said

“Looking at the label and what I paid for it, $14.99 per kilo. Less than local fishers here in Brisbane can get for their fish”

“How does this make sense?” Associate Professor Tibbetts asked.

“We’ve got this globe-trotting fish that ends up on the shelves for half the

price of what I can buy [locally], and we don’t know how or why,”

In 2016, one family-owned Australian seafood company sold 90 per cent of its seafood processing, wholesale and export business to a Chinese conglomerate.

The packaging industry in China receives government subsidies that reduce the cost to their customers and draws a global market to their shore. The cost of living is also a lot less in China than in most western societies, which supports income viability for the individual.

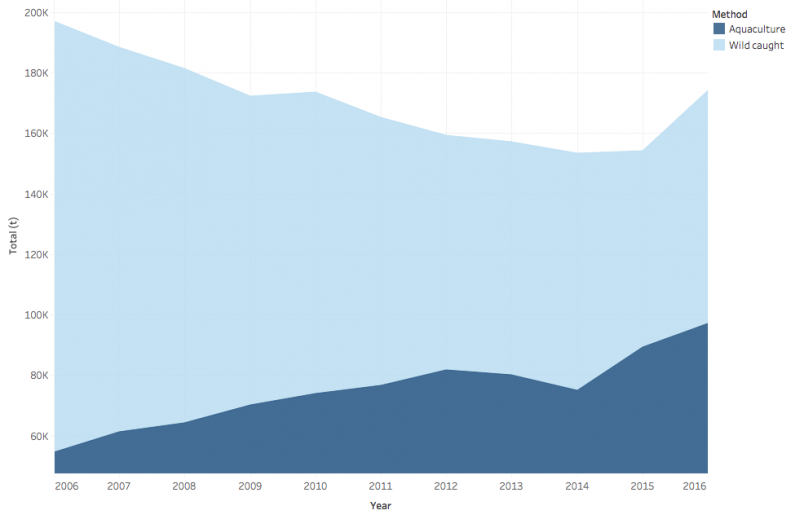

^ Total tonne (t) produced from Aquaculture and Wild Caught seafood industry Australia from 2006 – 2016

Early last year, the outbreak of white spot disease decimated prawn farms in southeast Queensland.

One of those farms was Gold Coast Marine Aquaculture, which lost almost 25 million black tiger prawns when it was forced to purge its stock following confirmation they had been infected.

General manager Alistair Dick has said the outbreak cost his company around $14 million, and forced a 12-month shutdown upon them.

He has no doubt that raw, imported prawns carrying the virus and used as bait were to blame.

However, he doesn’t think disrupting the seafood supply chain by banning the import/export trade is feasible.

“It’s really about making those trades [imports] safe,”

“Valid control mechanisms need to be applied to make sure we don’t import exotic diseases,” he said.

The flow of fish goes both ways, or rather, multiple ways.

“A lot of the high value, good quality products leave the country and a lot of that pre-packaged, ready to eat stuff, which is low value, low standard, is what people in Australia are getting used to”

“It’s very unfortunate,” he said.

Does it matter that Australians eat so much imported seafood while sending our best quality delicacies overseas?

The answers vary, and there are a great many considerations to be made before trying to answer that.

In 2009, members of the UN General Assembly revealed that food production would need to double by 2050 “to meet the demand of the world’s growing population”.

The import trade helps meet supply demand in Australia while simultaneously reducing the impact on Australian marine environments. However, it only exports the environmental degradation to other countries who may not have the resources to police the sustainability and food quality standards of fisheries or aquaculture farms.

Export trade is a steady source of income for local fishers who struggle to make a profit. Supply opportunities from Australian retail markets are limited and a high cost of living driven primarily by property prices contribute to this. However, labour conditions and end-user treatment of exported fish and shellfish are not guaranteed.

Associate Professor Tibbetts recently returned from working with local communities in the western provinces of the Solomon Islands.

When contrasting the two countries, he reflected upon the “relationship with nature, the intimacy, the belonging to land” and wonders whether we should be taking their lead in engaging with our environment.

“You have to get an understanding of nature and you have to get an understanding of where the food comes from and if you don’t have those things, we’ve lost,” he said.

“If we want to protect the future, if we want to look after responsibly,

our part of this planet, we have to start understanding things.”

Greenhouse gas emissions are a by-product of the global seafood supply chain but it is not the only challenge that needs to be addressed.

Scientists continue to research a more effective application of marine protected areas to maintain biodiversity while meeting fisheries demands.

Eutrophication (nutrient pollution), disease management, excess nitrogen and environmental restoration also remain issues within both fisheries and aquaculture industries.

Another major challenge is that a lot of aquaculture feed is made from fish meal and oil derived from what’s called “trash fish” – bycatch from deep-sea trawling.

On top of this, our oceans are warming and becoming more acidic in the face of climate change and an extensive plastic pollution problem continues to choke its inhabitants.

These considerations barely begin to unpack what is an incredibly complex issue that has a myriad of parties invested in its ongoing sustainability and success.

One thing is clear, however, there is plenty of fish in the sea – until there isn’t.

Kirsten Slemint

Kirsty is completing a dual Bachelor of Journalism and Bachelor of Science (majoring in Zoology) at the University of Queensland. With a passion for the effective communication of science, she has her sights set firmly on a career in documentary film production.