Fee hike could mean trouble for science students

A recent report by the Grattan institute has suggested that students studying certain areas to do not provide extensive public benefit should be paying more for uni. However, the justifications for this change may not hold true in certain fields, especially science.

A recent report released by the Grattan institute has suggested that science and law students around Australia should be contributing more to their university fees. The report cites low public benefit, attractive jobs, above-average pay and status as the reasons for this proposed increase.

The report bases its analysis on whether a student studying a degree will have higher public or private benefit once graduated and employed. It then concludes that degrees with a higher public benefit, such as nursing, should be subsidised more, since the government sees more significant return on its investment.

Those with high private benefit, such as law and science, should be subsidised less, as their university fees are supposedly a small fraction of their lifetime earnings.

“I don’t think the proposed change is too extreme,” says Peter Finneran, marketing and admissions manager for the University of Sydney Law School. “Law students already contribute a large amount of their university fees themselves and a large number of our graduates are finding jobs straight out of uni.”

This may not be the case for science students, as the post-graduate world of science may not be as ideal as the Grattan Institute seems to think. In a report released by the Department of Education Employment and Workplace relations titled ‘Australian Jobs’, science jobs are scarce in Australia, with some fields predicted to produce less than 5,000 jobs in 2016-17.

On the other hand, the DEEWR report showed that law was a different story. According to the report, 83.6 per cent of law students who graduated in 2010 were employed full-time four months after graduation.

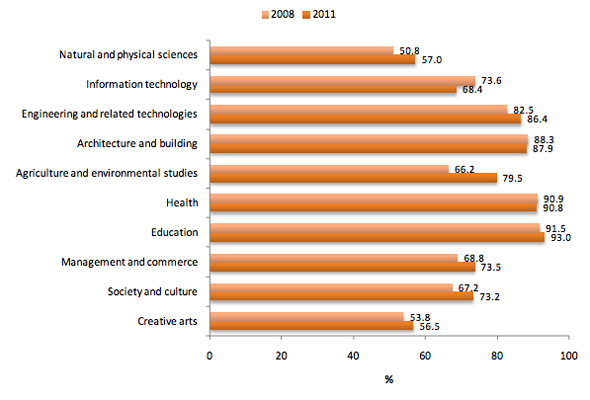

‘Beyond Graduation 2011’, a survey of Australian higher education graduates conducted by Graduate Careers Australia, also paints a dire picture for science graduates. It showed that in 2011, only 57 per cent of graduates in the natural and physical sciences were in full time employment — the second-lowest employment rate behind the creative arts.

Furthermore, the survey also showed that the median salary of these science graduates is lower than their more enticing counterparts. Science graduates were being paid around $65,000 per year, whereas others in fields such as engineering and management were being paid upwards of $73,000.

Percentage of bachelor graduates in full-time employment, 2008 and 2011. Data / graph courtesy of ‘Beyond Graduation 2011’ by Graduate Careers Australia.

“A lot of students in my classes ended up transferring from science to engineering, since they see more money in it,” said Ewan McAndrew, a recent physics graduate from UQ. “I graduated at the end of last year and still haven’t found a decent job. A large amount of jobs require postgraduate education as a minimum and I don’t know if want to be in the more debt required for an honors degree at the moment.”

Despite these drawbacks, according to the yearly report by the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education, science admission rates are among some of the highest of all the fields. In 2012, of all first-preference applications for the science fields, 100% of those were given offers, along with the third-highest (7.0%) increase in the number of offers since 2011.