A long wait home

“I DON’T usually like eating these types of salads,” Brendan said as he pointed at his plate with a plastic fork.

“It’s been a while since I’ve had a good serve of veggies though so I thought I’d better stock up,” he said

“She said there are pine nuts in it – they don’t taste too bad.”

The lively chatter that surrounded us and the quality of the food being served could make you think that you were enjoying a Sunday get-together with friends or family.

The reality was much different.

Brendan and I were sharing a meal underneath Turbot street overpass with many of the 19,000 people in Queensland who are considered to be homeless.

According to the Queensland social housing register, there are 18,738 applications which comprise of 37,688 individuals waiting to be assisted into suitable long-term accommodation.

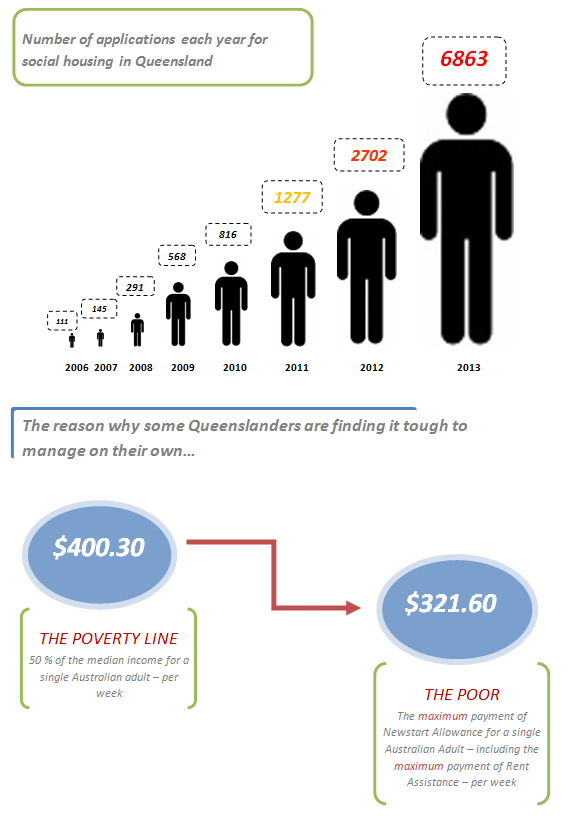

Despite Homelessness Australia’s claim of a 5.6 per cent drop in homelessness in Queensland since 2006, the number of applications for social housing in Queensland has almost doubled each year.

Chris Harkins, an electorate officer for Woodridge who works closely with Department of Housing, was able to offer an explanation.

“The reason that the data suggests the figures have been falling is due to the number of people who are transferred directly to the Rent Connect scheme from the social housing list,” she said.

Rent Connect is a government-funded rental scheme offering subsidised accommodation for those at risk of being homeless.

Rent Connect is a government-funded rental scheme offering subsidised accommodation for those at risk of being homeless.

But despite the best intentions of the scheme, the one-size-fits-all solution doesn’t address the needs of many applicants.

Because the accommodation is managed by private realtors, Ms Harkins says that prospective tenants are “still being screened more than they should be”, preventing many applicants from receiving the assistance they require.

“These are people with an income who are just managing to get by, but are prevented from entering a tenancy agreement because of their rental history,” she said.

“Rent Connect is one of the last safety-nets and if that fails then some people have nowhere else to go – just remember that these are the people diverted from the social housing register because they are not considered to be at high risk (of homelessness).”

Homeless or ‘very high risk’ applications are currently faced with an average waiting period of nine months before they receive assistance, however 513 of them have remained stagnant on the register for more than eighteen months.

According to a 2014 Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) report on poverty, a nationwide boost of 500,000 affordable rental properties is required to keep up with the growing demand on social housing lists.

“We know that exorbitant rents, particularly in our major cities, are placing a great deal of stress on families, with 47 per cent of low-income earners paying more than 30 per cent of their income in rent,” said Doctor Cassandra Goldie, ACOSS CEO.

“This is one of the major factors driving people into poverty.”

Of those who are living below the poverty line and at risk of experiencing homeless, 32 per cent are working in full-time or part-time employment.

Although homelessness is a complex problem to assuage, it is a state that many of us fail to understand just how easy it can materialise.

Rosie’s is a community organisation that has increased their street-relief services over the last 12 months in response to the growing number of Queenslanders requiring assistance.

Cat Milton, the spokesperson for Rosie’s Queensland said that “often very little exists between a homeless person and someone who is not homeless”.

“Most people are about a month away from homelessness – for many people a loss of income for four weeks is all it takes,” she said.

“It’s just a matter of a couple of experiences or a couple of safety-nets not being there.”

Ms Milton said that preventing homelessness is a complex issue that “crosses all human experiences”.

“In terms of a solution, there is no single answer to that – but it does require a holistic community-wide response,” she said.

“Generally, policies that promote a healthy and engaged community and increased social inclusion, then contribute towards preventing homelessness.”

Rosie’s’ primary focus on social inclusion is a crucial contribution, considering that over 10,000 single people in Queensland are struggling alone without suitable accommodation.

Brendan told me that he had left his family in Victoria and came to Queensland to “sort out his problems”.

“Living in Brisbane is tough, but luckily there are people who care,” he said.

Brendan is a regular patron of the soup-kitchen co-ordinated by Vital Connection, one of many organisations offering immediate relief to those experiencing life on the streets.

They have been serving free three-course meals underneath Turbot street overpass each weekend since 1995 and are planning to expand their service to include a rehabilitation program for young people who are ‘at-risk’ of homelessness.

Vital Connection spokesperson, Joanne Donaldson, said that “people still deserve compassion” despite the circumstances which led them to be homeless.

“We all need food, shelter and love, even if some of us have made some bad choices in life,” she said.

“It’s important that these people are not forgotten about– they’re just like you and me.”

Despite the Governments best efforts, it’s clear that a significant portion of our population is being left behind.

The Federal Government’s 2008 report on homelessness opens with the following statement: “In a country as prosperous as Australia, no one should be homeless”.

Perhaps our society could learn from the question that the Vital Connection volunteers ask as they heap food onto the plates of the hungry – “Is that enough?”

Maybe there is more that can be done to prevent homelessness.

Brendan shook my hand as he was leaving – “Look after yourself”, he said.

He meant it and repeated it again.

“Make sure you look after yourself.”

This post was originally published on Golden-I UQ 2014.