Breaking the cycle

LIKE most people, Jason never expected to be homeless. But eight months ago, the unexpected became a harsh reality.

It’s mid-afternoon in inner city Brisbane and Jason smiles to passers by as he raises The Big Issue in the air, brimming with positivity. It’s hard to believe the year he’s had.

In February, Jason, 38, spent the first night of his life on the street. For two months he slept on a bed of gravel by a car park in Fortitude Valley, living off two dollars a day.

“I had to lay down a blanket on the gravel so it wasn’t so bad. But when it rained it was awful, I didn’t have anywhere to go and I was so tired I couldn’t move.”

Jason had been made redundant when his job at Telstra was outsourced to the Philippines.

He’d been with them for one and a half years and ten years prior with a sister company in New Zealand.

Living off his savings, he took a break for a while and upon returning to Brisbane started looking for a job. Nothing. With no work and his finances dwindling, Jason was forced to leave his apartment; he had nowhere to go but the streets.

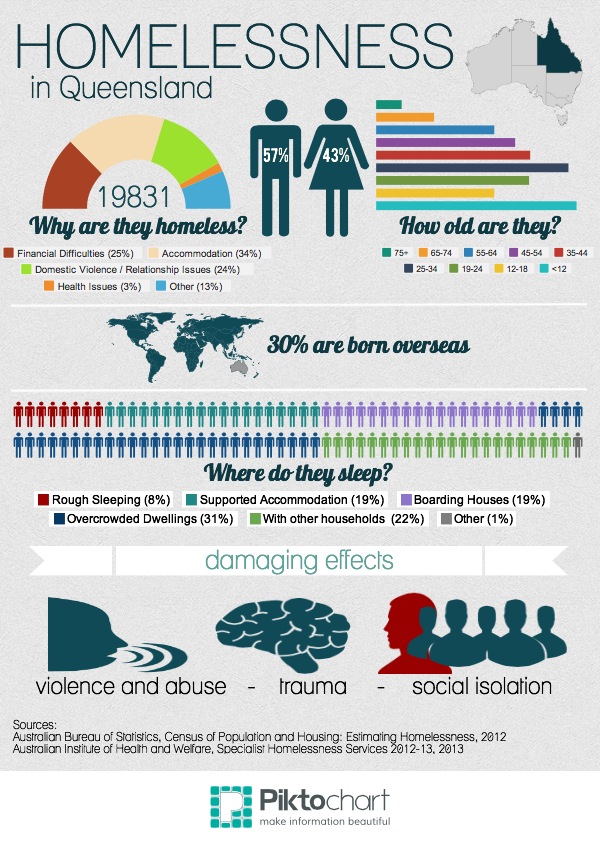

In Queensland, 45.8 in every 10,000 people are homeless, the third highest rate in Australia after the Northern Territory and ACT.

For every ‘rough sleeper’ there are many more on the brink of losing their beds. In fact, primary homelessness – sleeping on the streets or in improvised dwellings – accounts for only 8% of the homeless population in Queensland.

Most are in a state of flux known as secondary homelessness, moving between various forms of temporary accommodation; staying with friends or in hostels, youth refuges and boarding houses.

Lastly there’s tertiary homelessness, which describes Jason’s current situation. He lives in a single room in a private boarding house with communal bathrooms. The rent is $150 a week, which he pays for by selling The Big Issue, a non-for-profit magazine that provides jobs for homeless, marginalised and disadvantaged people. All additional money he makes goes to transport and savings – he’s put money aside to pay for a security course.

The causes of homelessness are as varied as the individuals it affects, each with their own story and baggage, both physical and emotional.

In Queensland, a chronic shortage of affordable and available rental housing, financial difficulties and domestic violence or relationship issues are the leading causes.

Unemployment and ineligibility for government payments as a New Zealander were the main factors that saw Jason end up on the streets.

But for many, there are underlying factors at play.

Intergenerational poverty, mental illness, economic and social exclusion all contribute to the issue both statewide and nationally.

Dr Catherine Robinson is a senior lecturer at the University of Technology in Sydney who has researched the traumatic violence that many people experience before and during homelessness.

“Whilst home for many is a site of care, safety and nurturing, for many who become homeless, home is the first site in which violent sexual and physical victimization occurs and often remains a conflicted and dangerous place throughout the life course,” she said.

Demi*, 24, is one of 8084 people experiencing homelessness in Queensland that are under the age of twenty-five. He suffers trauma from the violence and abuse he has experienced most of his life.

“I could have stayed with my father but he’s an alcoholic drunk who always used to abuse me. I didn’t wanna put myself in that situation,” he said.

He became homeless during high school and has been living in various states of homelessness ever since – in his car, temporary accommodation and on the street.

“My mum got sick, life threatening ill, and she couldn’t afford the rent. And because I’d dislocated my shoulder I couldn’t work anymore. When she went to live with her mum, I lied and said I had somewhere to go when I didn’t, for her sake of mind.”

Currently he’s in a boarding house, paying $130 rent a week.

“It [sleeping rough] is degrading. I took for granted how I used to live when I was younger.

But living on the street gave me some perspective. People take their houses for granted. I don’t take my place for granted. I see me living in a place as a privilege.”

The violence and abuse of his upbringing has affected him deeply, but it didn’t cease when he left home.

“It’s dangerous. If you’re on the street you don’t sleep till 3 or 4 in the morning when everyone else has gone to bed.

“I’ve been kicked in the chest when I was sleeping and people will call me a worthless piece of shit,” he said.

Physical violence is not the only impact; homelessness can be damaging psychologically.

Jason was able to avoid physical violence during his time sleeping rough, but experiencing homelessness has had severe psychological effects.

“I felt invisible. I even considered suicide for the first time in my life,” he said.

Research at the University of Queensland has shed light on the social impacts of homelessness and the struggles that people face on the fringes of society. Dr Tegan Cruwys from the UQ School of Psychology has studied the implications of social isolation on those experiencing homelessness.

“What we have observed is that over time people feel like outsiders: rejected and disconnected. These beliefs can become deeply embedded and make it difficult for them to connect with others,” she said.

The research also investigated ways of combatting social isolation in marginalised communities.

“Positive social experiences can contradict these beliefs. Social identification with a recreational group had benefits for participants’ health and wellbeing. Individuals who identify with a particular group, whether it is a sporting team, Canadians, or psychologists, feel that the group matters to them, and that they matter to the group.”

Mark McDonnell is a nurse and founder of West End charity organisation, Community Friends. The charity provides much needed support for over a hundred people every week, offering them 4-5 days worth of food. In addition to the immediate aid they provide, the organisation acts as a community network for the homeless and has helped many people to regain independence and autonomy.

“We help a wide range of people with varying needs. Some people will need assistance for the rest of their lives. Some will only need an occasional assistance to help them on their way. Some use what we offer, to create for themselves a better future.

“Most people come to us because of the food we give away, but it’s not all about the food. Knowing that there are people who will listen to them, who are concerned about their situation and will support them where they can is important,” he said.

Jason’s support has come from The Big Issue.

“To be honest, The Big Issue’s actually saved my life. Without it I’d probably be stealing or selling drugs, doing anything to make an income. In the second month, my mindset was actually thinking of stuff like that. But because Big Issue was around it’s saved my life, it’s put me on track, it’s paid my rent, allowed me to buy clothing.”

For most, breaking the cycle of homelessness is a long and difficult process.

Jason has managed to find a way off the streets, but he currently relies on the magazine for his entire income. However, with tight budgeting over the year he’s managed to save $650 for a security course and a further $400 for the security license.

It paid off. A couple of days ago he landed a security job at a hotel in Spring Hill.

“When they told me yesterday, I was screaming my head off I was so happy!”

So what are his plans for the future?

“To be honest, my ultimate dream when I was working was to become rich and save up and buy expensive stuff, live the rockstar life. But just seeing the homeless situation, it’s had such an impact on my life. My whole life has changed now.

This job I’ve got now, it’s not about saving up and getting rich. It’s about saving up and getting a van – making a food van for the homeless. That’s my ultimate goal now. Little by little we can make a change.”

* Demi has chosen this name for anonymity.

This post was originally published on Golden-I UQ 2014.