Legally blind

SARAH Boulton experiences life in a different way than the majority of us.

“When someone loses something, a limb, eyesight, it’s a loss for everyone, everyone in the family feels it. Some families fall apart debating whose fault it is, but not mine. My family got closer, that’s part of the reason why I don’t think it’s a bad thing I went blind.”

“I could honestly say it is the best thing that happened it me. I met my husband this way too. My husband was in the audience of one of my speeches.”

“I became more confident in who I was, I knew what I should be doing, so I got through this whole situation quickly, but it caught up with me a few years later.”

“But I’m just going to keep going, there is no point waiting for technology to help me. Yep, my vision is fading, but so what? This is a stepping stone for when I go totally blind.”

According to Karen Knight from Vision Australia (a not-for-profit organisation that provides various services for legally blind people) Sarah is one of the 60,000 legally blind citizens in Queensland; additionally there are around 300,000 people Australia wide that are registered as legally blind.

Having become legally blind at 25, Sarah is now living with the knowledge that one day, she can become entirely blind.

Right now, without any visual aids, Sarah’s left eye is only light-dark sensitive, while her right eye still has around 15% of her original eyesight. Sarah’s deteriorating eyesight is due to type 1 diabetes, a complication called diabetic retinopathy; she first noticed the condition when an area of her right eye’s vision darkened, this happened on a Friday when Sarah was 25, and her eyesight has declined since.

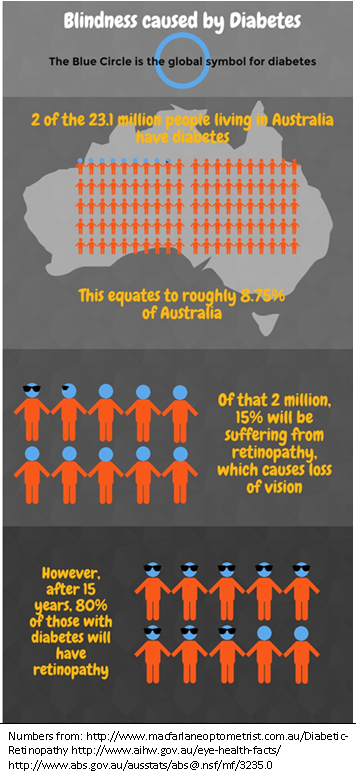

It is estimated that two million Australians have diabetes (both type 1 and 2). The Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle study found that 15% of people with diabetes had retinopathy.

According to The Australian Centre for Behavioural Research in Diabetes, diabetic retinopathy causes 17 per cent of all blindness and vision impairment and is the most common form of blindness in adults 20 -74 years.

Not being able to see may sound like a terrible way to experience the world, but Sarah was easily one of the brightest people I have ever met.

Starting from the moment I walked into her apartment that over looked the Brisbane River, her joyful personality was on show.

“Come in!” “Check out my view!” “Blind people always have the best views!”

Her apartment was tidy. A couple of red couches on one side, the kitchen on the opposite side and a dining table with a bright red salt shaker in the middle. The computer sat next to the dining table, it was on, but the screen was off.

“I thought you’d want to see how I use a computer, it’s called ZoomText, it blows everything up so I am able to read stuff, when I don’t want to/can’t read, Paul does it for me.”

Paul was the voice in the computer.

“In a way it’s kind of neat, I was born with eyesight and now I’m legally blind, I’m lucky to be able to experience the world in different ways.”

When asked how she became so comfortable with being blind – Brisbane born, Canada raised – Sarah had no problem explaining how she achieved her positive outlook on life.

But, as people would’ve probably guessed, Sarah wasn’t always this optimistic about her current situation. She admits having going through rough patches earlier in her life.

“I’ve thought about killing myself, but hey, I’m still here and you know, now all my other senses are sharper. My food probably tastes better than yours.” she joked. “I remember getting home [from the doctors] and was like, I can’t do anything, can’t walk, can’t do dishes, can’t find my cat, I even get lost in my apartment, but then when I unloaded the dishwasher, it took me a whole hour, the sense of accomplishment was amazing, then I wanted to try everything!”

“I never had time to think that I was about to lose my eye sight. It was that sudden. In a way, this was good to lose my eye sight as I would have had too much time to think about all of the things that I won’t be able to do again. And look at me now – my philosophy is that I can do anything you can do, I just have a different way of doing it!”

Mark, who has been married to Sarah for four years, says there are things Sarah does more efficiently than him.

“Her memory is fantastic, it may be that she had a good memory to begin with, but her memory has made it necessary for her to keep a lot more details, big schedules, where everything is and so on.”

“She actually does everything well, the only thing I have to be conscious of is putting back things where they came from.”

While memory does play a huge part in how Sarah performs her everyday tasks, she let me in on the secret in how she distinguishes between her belongings: elastic bands.

“Elastic bands allow me to distinguish between shampoo and conditioner, flavour of soups and so on.”

“It’s a misconception we need a lot of help, I lived by myself in Calgary for 3 years.”

Graeme Innes, Australia’s former Disability Discrimination Commissioner, agrees.

“The hardest thing a blind person has to tackle everyday is the negative attitude of general community, constantly making assumptions what we can’t do.”

“The important thing for people to know today is that we are no different to you, just be respectful.”

That doesn’t sound too unreasonable.

It seems like Sarah’s philosophy was summed up nicely at the end of our interview:

“You can sit and cry or you can get up and try.”

That doesn’t sound too unreasonable either.

This post was originally published on Golden-I UQ 2014.