Mental illness: under-reported, under-observed

IN 2011 the police found ‘Jane’, naked and fearing for her life on the streets of Brisbane. She told the officers that somebody, or something, was after her. Three years and more than 20 doctors later, Jane’s experience is evidence of an under-funded and under-resourced mental health system.

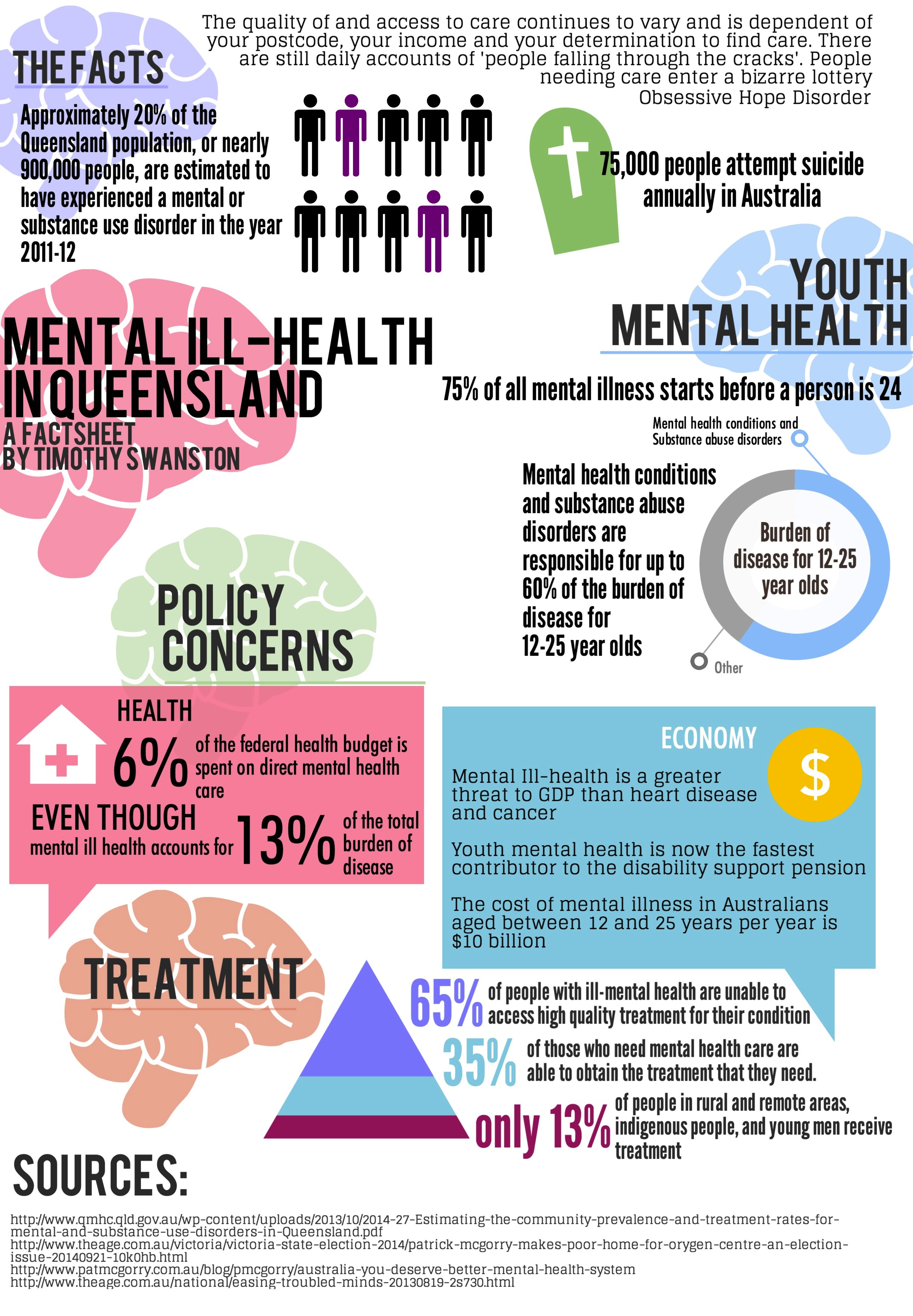

The Queensland Government say that they are ‘improving the quality, range and access to mental health services’. However, in Australia today, nearly 70-percent of people who need mental health care are unable to receive the quality of treatment that they need.

Jane is one of the 405,000 people in 2011 that are estimated to have experienced a moderate to severe mental or substance abuse disorder in Queensland.

Following the events of her manic episode, police took Jane to Logan Hospital, where she spent three weeks in the mental health unit.

“They didn’t give me a diagnosis, they just put me on anti-psychotic drugs for a few months. I was put on an involuntary treatment order so I had to take what was given to me, I had no choice on it.”

As part of Queensland’s mental health care infrastructure, patients are prescribed Involuntary Treatment Orders, or ITOs.

ITOs allow psychiatrists to monitor a patient’s condition, provide treatment that is non-consensual and take a person to an acute ward for treatment. Or as Jane puts it: “They take away all your freedom.”

Jane has been to hospital for the treatment of her Bipolar three times. She is increasingly frustrated at the lack of consistency and the quality of care that they provide.

“Every time I went to see doctors it was a different one. Pretty much they just dealt with medication, they didn’t really deal with the issues and they didn’t tell me what they thought was wrong.”

Jane wasn’t allowed to leave Logan hospital for weeks. During this time she begged the nurses there to let her go and see her children.

“They told me I wasn’t allowed to see my kids. It was really hard, and heartbreaking. I was crying every day and they just told me we can’t let you out until you stop crying.”

From July 2012 to June of 2013 more than 5000 Involuntary Treatment Orders were issued in Queensland

Professor Patrick McGorry, executive director of Orygen Youth Health and Australian of the Year in 2010, says that a reliance on ITOs is indicative of an under-funded system.

“For some people they are necessary, but the trouble is because of the underfunding in the system there is too much weight placed on last-resort type treatment, late intervention and more coercive treatment than is ideal.”

Across 2012 and 2013, over 2000 involuntary treatment patients absconded from the mental health facility that they were receiving treatment in.

A document obtained through an RTI search shows that Queensland Health identified the following as the main reasons for why patients abscond from mental health facilities:

“Discontent with being an involuntary patient, their treatment, or negative relationships with staff. [A] Fear of hospital setting or of other patients. Feeling trapped and confined,” the memorandum says.

In 2013, Queensland Health issued a directive for all 16 mental health facilities across the State to be locked.

“[It] is a disgrace in the 21st Century that facilities are locked. That’s just like a sledgehammer trying to crack a nut [and] it’s happening because of serious underinvestment,” Professor McGorry said.

Involuntary Treatment Orders are enforced through ‘Authority to Return’ (ATR) warrants issued by Queensland Health to the police.

Jim Papoutsakis, director of Queensland Police’s mental health division in Logan, says that police crews carry out ATR warrants.

“It’s a mechanism for Queensland Health to get the patient back to get further treatment. So it’s really not what we want, or what we think as police officers, this is a mechanism and we have to return that patient to the hospital,” Mr. Papoutsakis said.

“But naturally, if your mother had a mental illness would you rather have a police car parked in the front of your house or would you have an ambulance parked in the front of your house to take her to the hospital,” he said.

Doctor Steve Murphy, child and adolescent psychiatrist in private practice, says that ITO’s are a necessary part of mental health care.

“When people are sick they often don’t realise that and they can cause harm to themselves in moments of stress. It would be a very sad world where we didn’t have that ability to help people most in need,” Dr. Murphy said.

Professor McGorry calls this the broken promise of ‘deinstitutionalisation’. The failure of State Governments to build an adequate youth mental system in the past has meant that Queensland has had to place a significant emphasis on last-resort treatment.

“If all the other elements of the system were developed and function well, [ITO’s] would be much less needed. But unfortunately, although no one thinks it is the right thing to do, and all the evidence points the other way, because of the lack of investment that is what is happening,” Professor McGorry said.

“I think we’ve seen mental health go backwards in a major way. There’s a lot more investment in the acute hospital end of things and an overall lack of investment globally – it is still way underfunded.”

Following her treatment at Logan hospital, Jane told the nurses that she still needed help and that she didn’t feel ready to leave.

“They said that they have more severe cases that we have to deal with, surely your GP can handle it.”

Jane has been out of Logan hospital for a few months now. Before the interview, she was laughing and playing with her daughter.

“They should probably give more help with the core issues rather than just saying you’re a druggie, or you’re an alcoholic or you’re an attention seeker. They should see us as people rather than just something in the paperwork.”

This post was originally published on Golden-I UQ 2014.