Paramedic pain

CONSTABLE Leanne Hay knows to expect a bit of chaos when she starts her shift for the Gold Coast Police. Fatalities are a sombre reality in her job as a police officer. But there are some callouts which resonate with her long after the shift is over.

“There was this one call which we knew was an attempted suicide. When my partner and I turned up at the house, we heard this grunting noise like the sound of a man getting out of a chair, and a part of you hopes that what it is.”

“But when we went inside we saw him hanging from the ceiling.”

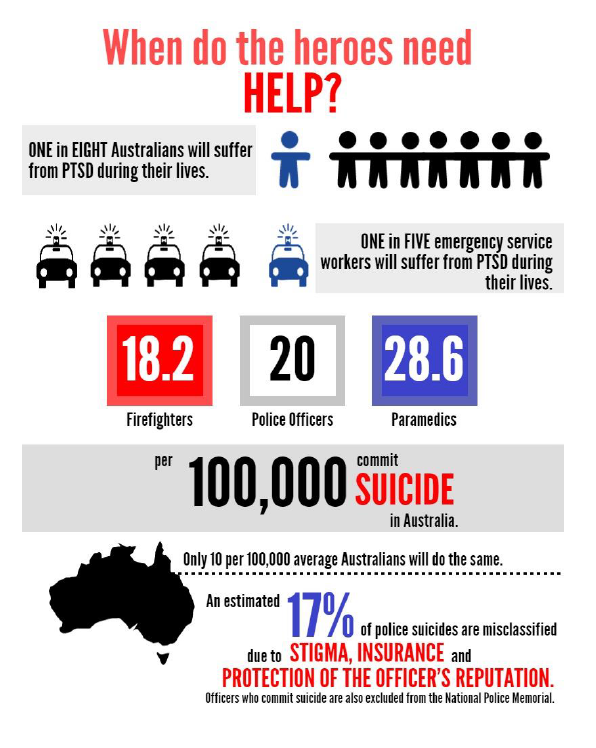

When accidents are reported on by the media, little coverage is spared for emergency workers where death and carnage are part of their job description. However, it has been suggested that up to 20 percent of emergency service workers suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder at some point during their careers.

Between 2010 and 2012, eight paramedics in Victoria committed suicide. The suicide rate among paramedics was 20 times higher than that of the general public.

Fortunately, the situation in Queensland is not so dire. Priority One is a peer-support program initiated by the Queensland Ambulance Service that focuses on preventing the onset of mental health issues.

John Murray is an ex-paramedic who now works as a counsellor for Priority One. He believes the success of the program lies on its empathetic nature.

“What makes Priority One unique is that we’re always on the road, we’ve been paramedics before becoming counsellors, so we’ve been there before and we know how it feels,” Mr Murray says.

“We want to help paramedics sustain themselves in the work they do and acknowledge how they build resilience, as well as educate them on how to look after themselves rather than deal with mental illness when it happens.”

“We’re more interested in putting a fence at the top of the cliff, but there’s always going to be an ambulance at the bottom just in case people fall over.”

The Australian government has given Priority One a $20 million budget. Peer support officer Ken Hall explains that the reason the program is given much more funding than similar support networks in the police and fire departments is because they have the results to prove its success.

“We’ll support our colleagues in both professional and personal conflict. There are psychologists and counsellors, as well as peer support officers on call 24/7.”

“The program is based on self-referral and self-action, but peer support officers will direct paramedics in the right direction.”

“Weakness is not stigmatised, it’s very accepted and the program is very interactive.”

The success of the program is evident as only 0.5% of all paramedics in Queensland have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. But given the uncontrollable and unpredictable nature of PTSD, Constable Hay finds that sometimes resilience is not enough.

“The guy was only young, and he was struggling as I tried to cut the noose from around his neck.”

“I accidentally cut his arm with the knife, and the cut was pretty deep. It wasn’t until we had him restrained on the floor that I realised in the process I had cut myself with the bloodied knife too.”

Firefighter Mark Alfredson can relate to these kinds of traumatic incidents. He explains that once he had six fatalities in three weeks.

“That definitely puts a bit of a bump in you. It’s about what type of accidents you attend more than anything, road crashes make you burn out pretty quickly.”

Similar to Priority One, FireCare is a counselling service available to firefighters and their families.There are also peer support officers who can be consulted after fatalities.

“FireCare is used a fair bit but peer support is definitely underutilised because you don’t want to be seen as weak.”

Mr Alfredson laughs when I ask whether the FireCare budget is similar to Priority One. “Nowhere near it.”

These days, firefighters are often deployed to accidents before paramedics. They are the first to witness carnage and the ones left to clean it up too, which is why firefighters are becoming more susceptible to PTSD.

Constable Hay knows that the effects of a traumatic job can have a ripple effect into the personal lives of emergency personnel.

“The guy who’d attempted suicide was a drug user so all of a sudden there was this real threat of HIV or AIDS because our blood had infused”.

“I had to wait six months before the test results came back, and I found myself really stressed at home.I had to put my life and my marriage on hold after this one job”.

Peer support is available for police officers. Ex peer support officer Leonie Burridge backed out of the role but says that officers know there’s help available.

“It’s accepted in the police force that sometimes you need to ask for help.”

“You can talk to an officer or a colleague, but I still don’t think that the peer support officers are used enough.”

So what sort of support did Constable Hay receive after that particular incident? “An overwhelming amount” she exclaims.

“I had counsellors and the hospital constantly checking up on me, I didn’t even need to ask.”

However, she is quick to point out that response is an extreme end of the spectrum.

“My next job was to a really serious car accident where we were first on the scene. The bodies were pretty mangled, it was really difficult.”

“After that accident, there was nothing. I suppose it just falls through the psychologists’ net because there’s so many crashes, but you do feel a bit forgotten.”

The amount of trauma exposure experienced by emergency service workers means that they are at a serious risk of developing PTSD. But until the Australian government collects statistics on the mental health of emergency service workers, PTSD will remain as a deadly taboo.

This post was originally published on Golden-I UQ 2014.