Surviving the guilt of living

MICHAEL Callaghan and Mathew Tait were best friends. They were never strong believers in coincidences. But by the age of 14 the schoolyard mates from New Zealand’s North Island had both been diagnosed with cancer.

Michael and Mathew were 11-years-old when Mathew was diagnosed. Michael supported his best friend for three years before he was also diagnosed with a cancerous Germinoma brain tumor at 14.

Besides sinus problems, Michael was a typical sports-mad teenager. He was on his way to a golf tournament with his father when he got a painful migraine and went to the GP. As Michael sat in the car waiting, his mother and doctor noticed that he was acting strange, so the doctor advised him to go to the hospital.

As Michael walked through the hospital car park he was uncontrollably walking into cars. An MRI scan soon revealed he had cancer, which was cutting off the fluid around his brain.

“One minute I was enjoying life, sports and hanging with my mates and the next I was on a plane to Starship [hospital] to determine my prognosis,” says Michael.

Michael went through radiation treatment for one year before having a relapse. He then went through intense chemotherapy for another year. During his treatment Michael was told that his best friend had passed away. He was devastated but Michael was not well enough to fly home to attend the funeral.

“It was one of the biggest regrets of my life.”

A few months after Mathew’s death, Michael was cleared of all the cancer. But life after cancer proved to be difficult.

Katie Clift from Cancer Council Queensland says that the impact of cancer and treatment on a person can vary greatly, as cancer survivors try to deal with insomnia, confusion or depression.

These emotions are common and often talked about in therapy sessions, which helps the survivor to overcome these feelings. But there is an emotion that has many survivors confused and ashamed to talk about.

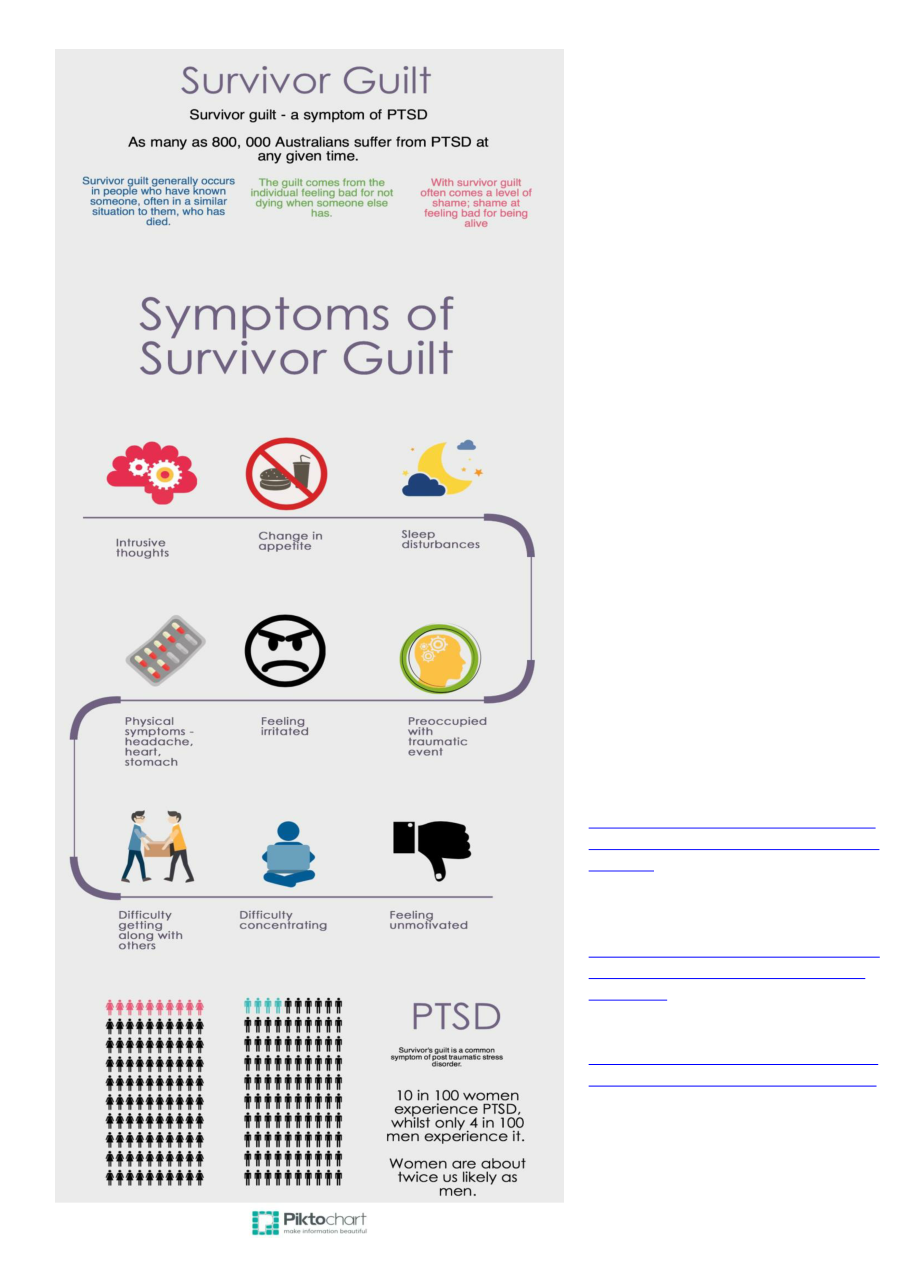

Survivor guilt. It’s a misunderstood emotion. Why not me? Why them?

They’re the questions that often go unanswered.

This feeling of guilt is not only common among cancer survivors; it’s a common feeling of guilt that comes from an individual feeling bad for not dying when someone else has.

Laura Storey from CanTeen Queensland strongly feels that survivor guilt is a very hidden emotion. Survivors won’t share what they are feeling with anyone, as they fear being judged by their tangle of emotions.

“I personally think survivor guilt is a real issue and that, particularly in support groups, it needs to be raised forcibly.”

Survivor guilt can be experienced at different levels. Laura says that some experience it for a just a few days post-bereavement, while others experience it to the extent of depression and post-traumatic stress.

Abby Holme was a 20- year-old, healthy, ambitious teacher when she was diagnosed with Meningococcal Septicaemia. Originally thinking she had come down with a bad flu, Abby was lucky to have been diagnosed so quickly.

“My South African doctor had some experience with the disease and immediately administered IV antibiotics.”

As Abby was diagnosed and treated almost instantly, she was back in good health within six months. Though she was no longer physically sick, Abby was emotionally scarred. She felt guilty and undeserving for living when others hadn’t been so lucky.

“I felt guilty after seeing terrible things happening to others on TV [from meningococcal] and not really liking my school principal, who essentially saved my life…I felt like I had to be exuding gratitude, zest for life and achieving something great, but I am not like that by nature.”

There is a sense of implied comparison among people who have suffered parallel ordeals. When Abby compared her experience with others it was only natural; however, it was affecting her in more ways than people knew.

“I felt sick and not deserving of being one of the ‘lucky ones’…I felt like a fraud.”

Talking about it was one of the hardest things Abby ever had to do. She didn’t want to flaunt her health to people who had physically suffered much worse, but she was psychologically suffering herself.

Abby tried to ignore these feelings of guilt for many years. She would do things to try and make herself feel truly alive, and eventually she felt worthy of being saved.

“I travelled to far flung places and did crazy things just to really feel what alive was. Then I returned home and settled down to find out who I was and realized that I was complete and a good person who was worthy of being alive.”

For Abby, survivor guilt was all about self-esteem. Once she felt worthy of being just whom she was – the pressure and guilt lifted. But it’s not that simple for some.

Lizzie Hoare was a fun-loving 17-year-old when she was on her way to Byron Bay with a two of her closest friends.

Lizzie, Megan, and Jaz were almost at Byron Bay when their world collapsed.

“My life flashed before my eyes. One minute we were celebrating our final weeks of school, and the next my best friend was fighting for her life.”

Lizzie and her friends had almost arrived in Byron Bay when Jaz’s Holden Barina swerved off the road and hit a tree.

“It happened so quickly, I have very little memory of the actual crash, besides the noise of smashing glass and the bonnet crushing.”

Lizzie walked away with minor injuries. Megan and Jaz were both in a critical condition, but Jaz sadly did not survive. Lizzie struggled with the loss of her best friend, and struggled to comprehend why she had been lucky enough to walk away.

“I couldn’t get the image out of my head. Although I didn’t physically struggle, I mentally struggled for quite a while.”

The guilt made Lizzie retract from her everyday life with her family and friends. She didn’t want to speak to anyone about it, so eventually the guilt consumed her. The survivor guilt led to Lizzie suffering Post Traumatic Stress Disorder for a year after the accident.

“I had horrible flashbacks and nightmares and I barely ate. I felt trapped and like I was constantly fighting an uphill battle with my thoughts.”

Lizzie’s family was desperate for her to speak out. They could notice her wellbeing deteriorating and decided that she had been withdrawn for too long so they insisted she see a therapist.

Therapy sessions clarified the feelings of guilt that Lizzie had been feeling. They allowed her to understand what she was feeling and why she felt that way.

“After finally being able to understand what I had been feeling for the past year, I could eventually think clearly again – I wished that I had spoken out along time ago.”

Survivor guilt is a real issue that often goes unnoticed. People tend to isolate themselves when feelings of guilt arise, much like the survivors above; this is why more environments need to be made where this matter is being powerfully raised.

This misunderstood emotion needs clarification but moreover, it needs light shed upon it, so those that are suffering know they’re not alone.

Anyone feeling survivor guilt can contact Beyond Blue on 1300224636.

This post was originally published on Golden-I UQ 2014.